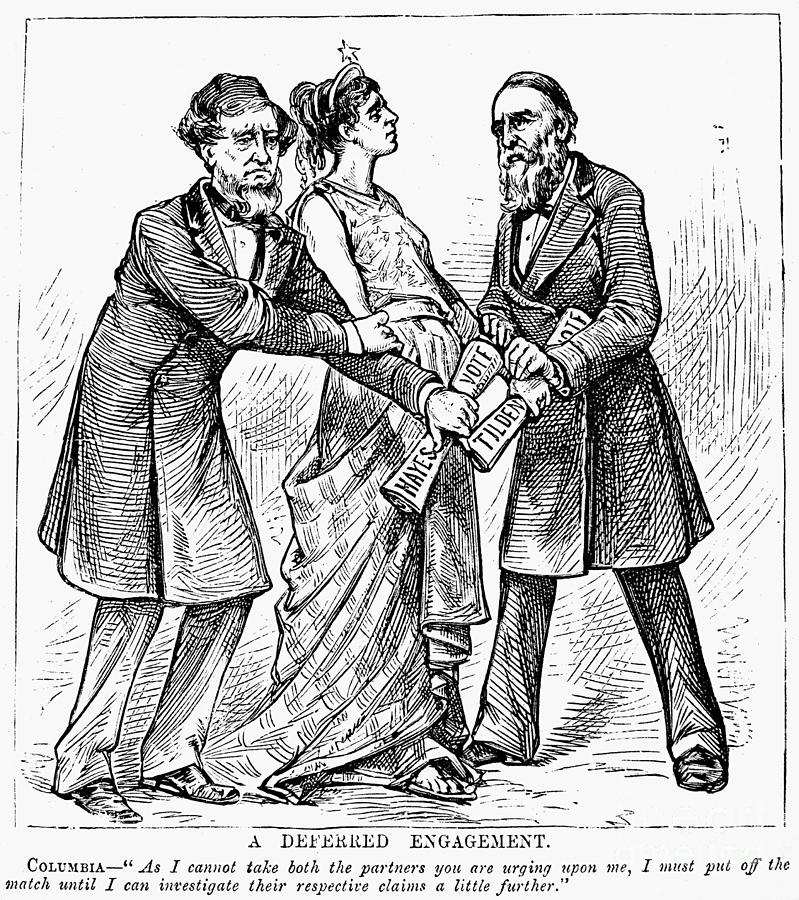

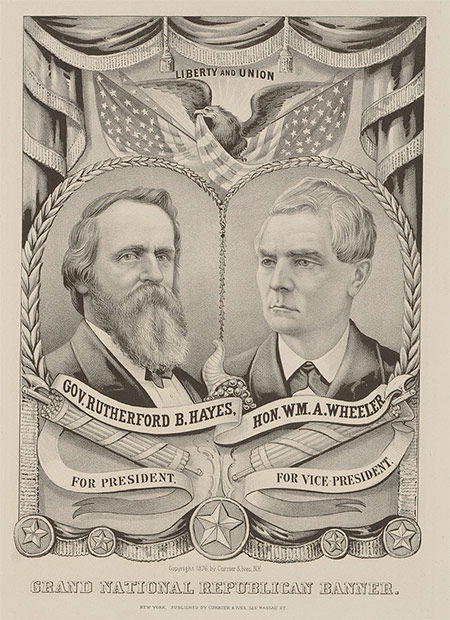

Las elecciones presidenciales de 1876 fueron unas históricas caracterizadas por el fraude, la intimidación y la violencia. Los Republicanos nominaron como su candidato al gobernador de Ohio Rutherford B. Hayes, un político insípido, pero integro. Los Demócratas nominaron al gobernador de Nueva York Samuel J. Tilden. Ambos favorecían el gobierno propio para el Sur (es decir, no interferir ni intervenir en los asuntos políticos del Sur) y, además, la reconstrucción no era una de sus prioridades.

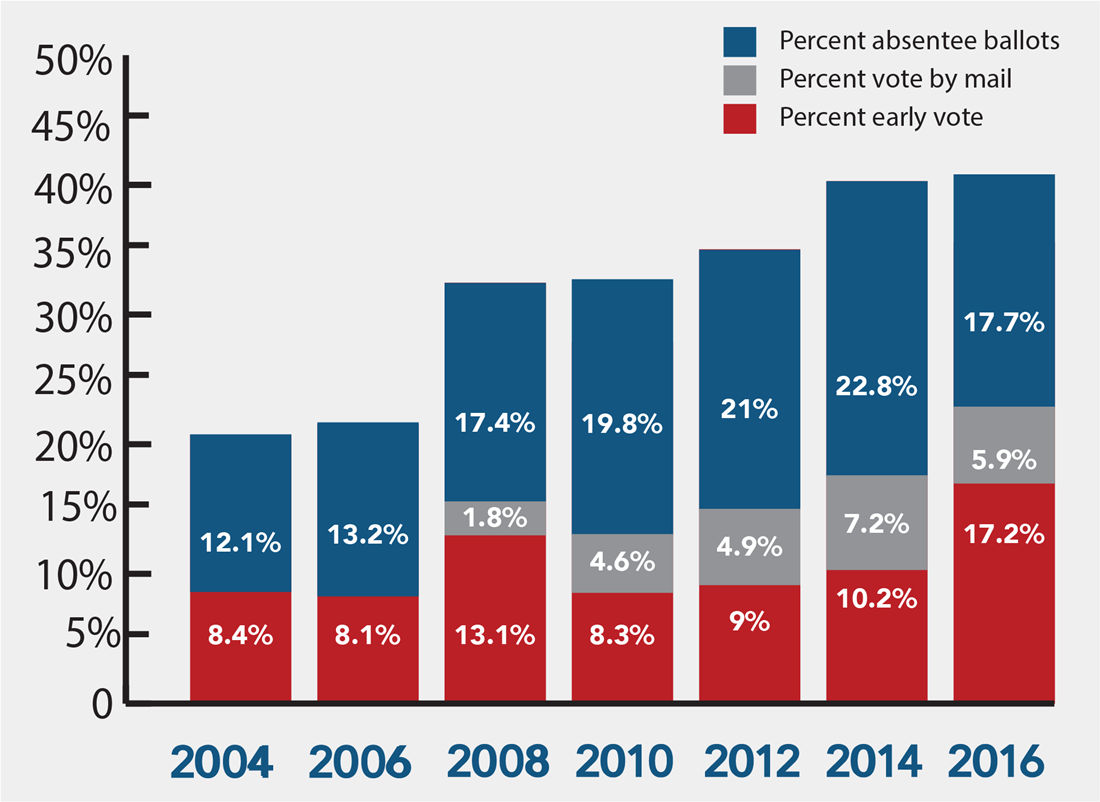

Esta elección ha sido una de las más cerradas en la historia de los Estados Unidos. Hayes obtuvo el 48% de los votos populares y 185 votos electorales, mientras que Tilden le superó en votos populares con el 50% de éstos, pero sólo alcanzó 184 votos electorales. Ninguno de los dos candidatos obtuvo el número de votos electorales necesarios para ser electo presidente, lo que provocó una seria crisis política. Para resolver esta crisis el Congreso nombró un comité compuesto por cinco senadores, cinco representantes y cinco jueces del Tribunal Supremo, ocho Republicanos y siete Demócratas. El comité votó en estricta línea partidista a favor de reconocer la elección de Hayes, lo que generó las protestas de los Demócratas. Éstos controlaban la Cámara de Representantes y amenazaron con bloquear la juramentación de Hayes. Para superar esta crisis se llevaron a cabo negociaciones secretas que culminaron con un acuerdo en febrero de 1877: los Demócratas aceptaron la elección del Hayes a cambio de que éste nombrara a un sureño en su gabinete, no interfiriera en la política del Sur y se comprometiera a retirar las tropas federales que quedaban en el sur.

Poco tiempo después de su juramentación como Presidente de los Estados Unidos, Hayes ordenó la salida de las tropas federales de Florida y Carolina del Sur. La salida de los soldados conllevó la eventual derrota de los gobernadores Republicanos de ambos estados. Al adoptar una política de no interferencia en los asuntos del Sur, los Republicanos abandonaron a los afroamericanos. Aunque formaban parte de la constitución, las Enmiendas 14 y 15 quedaron sin efecto en el Sur porque fueron sistemáticamente ignoradas por los gobiernos sureños. Con ello murió la era de la Reconstrucción y se inició una era vergonzosa caracterizada por la supremacía de los blancos, la violencia racial, la violación sistemática de los derechos de los ciudadanos afroamericanos y la segregación de los negros.

Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite administering the oath of office to Rutherford B. Hayes, 1877.

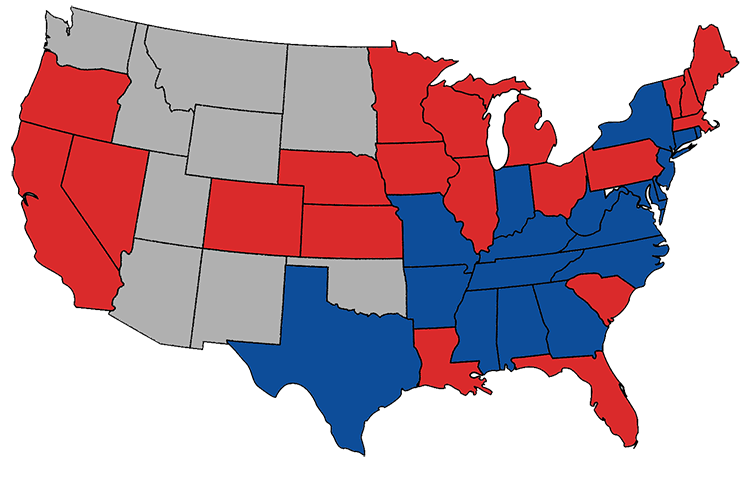

The Presidential Election of 1876

In the summer of 1876 the United States celebrated a centenary of independence. Although it was a jubilee year, the American Republic was also deeply troubled. The desperate battles of the Civil War had ended more than a decade before; yet Abraham Lincoln’s call for ‘malice toward none’ remained an unfulfilled appeal, as Federal troops continued to occupy some of the former Confederate States. President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term of office was drawing to a close under a barrage of criticism directed at corruption in his government. The coming Presidential election would take place in November.

It promised to be an exciting fight, but no one foresaw that the struggle between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel J. Tilden would result in an unparalleled scandal and bring America perilously close to another civil conflict. Indeed, the roots of the dispute were firmly woven into the Civil War and its tragic aftermath.

On April 9th, 1865 General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia and the guns at Appomattox stopped firing. The Civil War drew to a close. In four years of grim fighting the troops of both sides had developed a respect for each other, a bond of harsh experiences mutually endured. Now Yankees shared their rations with Confederates and traded wartime stories.

The day after the surrender, Abraham Lincoln returned to Washington after a visit to Richmond. A wildly cheering crowd called for a speech, but the President demurred. Instead, he asked the military band to strike up ‘Dixie’. For a brief moment there seemed to be hope of genuine reconciliation. It was unquestionably Lincoln’s fervent hope. Then, only days later, John Wilkes Booth fired a fatal bullet into the President’s head at Ford’s Theatre in Washington.

With Lincoln’s death, the ‘Radicals’ in the Republican Party gained the upper hand. For men like Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the South fully deserved the revenge they had planned. The bitter years of ‘Reconstruction’ followed. Government tax-collectors enjoyed a bonanza below the Mason-Dixon Line. General Lee’s magnificent home at Arlington was seized for taxes. Properties worth thousands of dollars were sold for a few hundred and Federal Treasury agents laid claim to supposedly abandoned land. Even General William Tecumseh Sherman, whose army made the famous march from Atlanta to the sea, burning and destroying everything in its path, spoke in compassionate terms to a veterans’ gathering shortly after the war:

It was in this atmosphere that white Southerners fought to regain control of South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Florida and other states of the former Confederacy; the newly emancipated slaves fought for a place in a society previously denied them; and political scavengers fought to hang on to the spoils of war. Gradually, however, the South returned to the control of its native white population. In doing so, it became more solidly attached to the Democratic Party than ever before.

Due to the presence of Federal troops and officials in positions of power, Ulysses S. Grant was able to carry eight southern states for the Republican Party in the Presidential election of 1868. Grant won a second term in 1872, but this time only six southern states were in the Republican camp. The grip of Radical Republican power was fading. Perhaps more significant, the immediate post-war zeal in the North for African-American welfare had diminished.

Republican election poster, 1876.

As the election of 1876 approached, Grant’s Republican administration reeled under a heavy attack by the press when a great whisky scandal broke. Western distillers had been flagrantly evading Federal taxes, and Grant’s own private secretary, General Babcock, was implicated. The President’s enemies gleefully pointed to corruption in the White House. Instead of dissociating himself from Babcock, Grant leaped to his defence.

Indeed, Grant displayed an almost incredible loyalty to dubious colleagues during his Presidency. His support of Babcock largely contributed to an acquittal. But this was just part of the rapidly mounting troubles faced by the Republican Party.

In March 1876, just eight months before the election, Secretary of War William Belknap was charged with malfeasance in office by the House of Representatives. Rather than remove Belknap from his post, Grant merely accepted the cabinet member’s resignation. One month later it was James G. Blaine’s turn to embarrass the Administration. As Republican leader in the House of Representatives, Blaine was in a most influential position. When the press charged that he had taken favours from the Union Pacific Railroad, the tag of ‘Grantism’ received new life as a synonym for political avarice.

The scandals could not have come at a more inopportune time, for the Republicans desperately needed a politically untarnished standard-bearer in the coming election and Blaine was a strong candidate. Despite the publicity, Blaine’s name was prominent when the Republicans met at Cincinnati, Ohio, on June 14th to nominate a contender for the Presidency. Recognising that public attention had to be focused on something other than the Administration’s record, Blaine attacked the South and stirred up fears of a new war. In doing so, he alienated those members of his party who sought a genuine rapprochement with the old Confederacy. On the seventh ballot, he lost the nomination to a ‘dark horse’ candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio. Hayes was a compromise between the extreme wings of the Party. Above all, his personal record and political integrity could not be seriously challenged.

The 53-year-old Hayes had a good, if not spectacular, background. Born in Delaware, Ohio, he had been raised by a widowed mother who, fortunately, enjoyed financial security. He received a degree from the Harvard Law School in 1845 and subsequently accepted a number of fugitive slave cases. During the Civil War, Hayes rose to the rank of brevet major-general of volunteers, participated in many actions and was severely wounded. While the war still raged he was elected to Congress. He was later elected Governor of Ohio on three separate occasions and put through a number of reforms.

In accepting the nomination, Hayes vowed to end the spoils system and called for an end to ‘the distinction between North and South in our common country’. This conciliatory statement was in sharp contrast to Resolution Number 16 of the Party Platform which went so far as to question the loyalty of the Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. This allegation reflected the presence of Congressmen who had fought for the Confederacy.

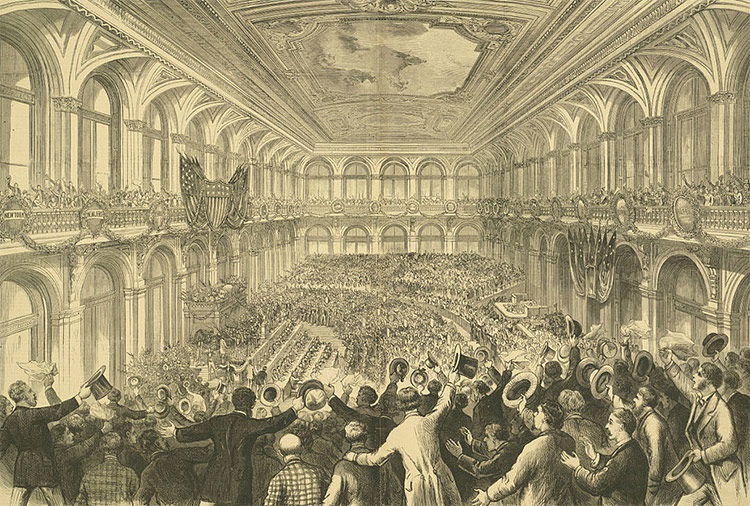

The Democrats had no problem in devising their campaign strategy. The entire nation was aware of the Administration’s shortcomings. Corruption was the issue and the Democratic Party promised reform. On June 27th they held their convention in St Louis, Missouri. In an auditorium jammed with 5,000 people, Governor Samuel J. Tilden of New York scored a landslide victory on the second ballot.

Samuel J. Tilden is announced as the Democratic presidential nominee.

Tilden was a unique figure, and certainly one of the most interesting to cross the American political scene. This frail, cold, articulate bachelor commanded a crusading zeal from his supporters. As a boy, Tilden was withdrawn and showed little inclination to mix with young people. Politics, however, fascinated him and his father fostered that interest. At the age of 15 he used his own money to buy Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. By 1841 he was a qualified lawyer with a continuing and consuming interest in politics. His brilliant grasp of political matters brought him to the attention of Democratic leaders who sought his counsel. For some time Tilden studiously avoided candidacy for high public office, but his own abilities soon brought him national recognition.

A particularly significant event was Tilden’s exposure and prosecution of New York’s notorious racketeer, ‘Boss’ William M. Tweed. His popularity soared and he was elected Governor of New York. Then he broke up the Canal Ring, a group of crooks and unscrupulous politicians. Tilden’s name became associated with integrity in politics. This was just what the Democratic Party wanted as a contrast to the Republican Administration.

The battle lines were clearly defined. Left to themselves, it is possible that Hayes and Tilden might have kept the election campaign free from distortion of facts and bitter personal invective, but it was not to be. Tilden was subjected to a number of damaging of charges. There seemed to be no limit to the accusations: that he was a liar, swindler, perjurer, counterfeiter and even an absurd claim that he had been in league with the infamous Tweed. In line with their basic campaign strategy, the Republicans alleged that Tilden had supported the Confederacy, the right of secession and the continuation of slavery. This all stemmed from his opposition to Lincoln in 1860, but that was because he was a Democrat and feared a Republican victory would bring disaster to the United States. This feeling had no bearing on his fundamental loyalty to the Union, and once the war began he had urged the quick suppression of the Confederacy.

As election day approached, excitement grew with each rally and parade. It was, after all, the centenary of American independence. Even politically apathetic citizens came out for Hayes or Tilden with great enthusiasm. But on polling day, November 7th, calm prevailed as people made their way to voting centres. It was a stillness soon to be shattered. Hayes’ hopes began to sink as swing states such as Connecticut, Indiana and New Jersey went to Tilden. When New York finally fell into Tilden’s camp, Hayes admitted defeat to those around him and went to bed.

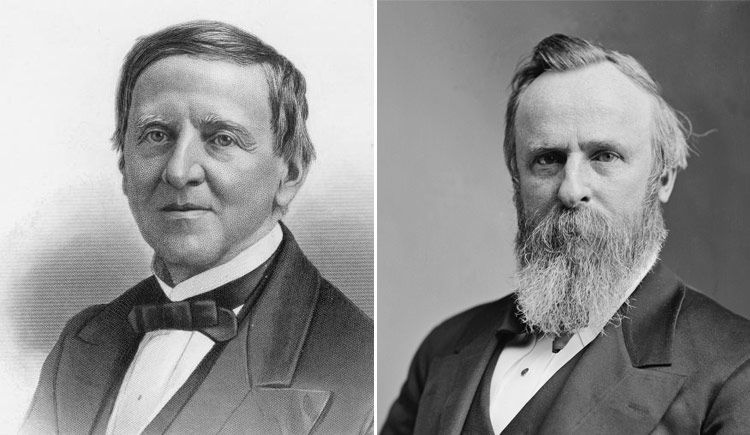

Tilden was not only leading in the popular vote: he had 184 of the far more important electoral votes to Hayes’ 166. The 19 votes of South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana were had not yet been declared, but they were in the heartland of the Democratic South. At the Republican National Headquarters, exhausted and dispirited party workers began to go home. On the morning of November 8th, the press of both parties was crowded with news of Tilden’s victory. Even the militantly Republican New York Tribune conceded the election.

The New York Times, however, would do no more than admit a Democratic lead. Two days after the election, John C. Reid, the newspaper’s influential editor, sat in the editorial room with two assistants. It was after 3am when a message arrived from the State Democratic Committee: ‘Please give your estimate of the electoral votes secured by Tilden. Answer at once.’ Reid was astounded. If they urgently needed such information, then the Democrats were not certain of victory. In a matter of minutes he conceived a scheme to wrest the election away from Tilden and put Rutherford B. Hayes into the White House. Tilden had 18 more electoral votes than Hayes, but if the 19 from South Carolina, Louisiana and Florida were secured by the Republicans, Hayes would win by one vote, 185 to 184.

Samuel J. Tilden (left) and Rutherford B. Hayes (right).

Reid, accompanied by a Republican official, hurried into the night and awakened Zachariah Chandler, National Republican Chairman. Chandler agreed to Reid’s proposal: telegrams must be sent immediately to Republican officials in the three states, with the following message: ‘Hayes is elected if we have carried South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana. Can you hold your state? Answer immediately.’ The meaning was clear: those states were to be held at any cost. At the same time, Republican headquarters proclaimed Hayes’ election.

The key to the plot’s success lay in the state canvassing boards. They had the power to certify the votes and cast out those that, in the board’s opinion, were questionable. The need for absolute honesty by the boards in exercising their power was self evident, but the personnel of some made comedy of that requirement. Of course, all of the boards were Republican and backed by Federal troops.

Initially, Hayes dissociated himself from the plan, saying: ‘I think we are defeated … I am of the opinion that the Democrats have carried the country and elected Tilden.’ A few weeks later, however, he changed his mind: ‘I have no doubt that we are justly and legally entitled to the Presidency.’

From the beginning there was an outside chance that Hayes could have carried South Carolina and Louisiana on the strength of votes from African-Americans and ‘carpetbaggers’ (a pejorative term for Northerners who moved South during the Reconstruction). Florida’s heavily Democratic white majority, however, made that state a dim prospect for Republican hopes. But they had to have Florida or Tilden would win by 188 to 181. During the actual election campaign, all three states witnessed a wide variety of attempts by both sides to cow voters and fraud was rampant. In one shameful tactic, the Democrats tried to distribute ballots with the Republican emblem prominently displayed over the names of Democratic candidates. It was worth the chance in the hope of picking up votes from illiterate voters. On the Republican side, one inspired person devised ‘little jokers’. These were tiny Republican tickets inside a regular ballot. A partisan clerk could slip them into the ballot box with little chance of being detected.

In Louisiana, Tilden held a comfortable majority over Hayes. And in New Orleans, the Democratic elector with the smallest plurality had more than 6,000 votes over his Republican opponent. The canvassing board solved the problem in that state by simply throwing out 13,000 Tilden votes against only 2,000 for Hayes. Then the electors for Hayes were certified.

The prelude to the election in South Carolina was a bloody affair. The Governor was Daniel H. Chamberlain of Massachusetts, a strict dogmatist on the race question and thoroughly loathed by white South Carolinians. In addition to the Presidential election, there was a gubernatorial race. The Democrats were running a war hero, former Confederate General Wade Hampton. ‘Rifle clubs’ were organised over the entire state by Hampton’s supporters and there were numerous clashes with African-American groups. As far back as July 8th, there had been a sharp fight in Aiken County at which African-Americans suffered a severe defeat. Chamberlain appealed to President Grant for help. Grant described the rifle clubs as ‘insurgents’ and sent all readily available troops to South Carolina. The resultant fury at this action was compounded when the Republican canvassing board ensured the certification of Hayes’ electors.

Florida was the most critical problem. As the polling booths closed, each side claimed victory. Once again, the canvassing board held the decision in its hands. The three-man board was dominated by two Republicans, Florida’s Secretary of State and its Comptroller. The third man was the Democratic Attorney General. The board had the right to exclude ‘irregular, false or fraudulent’ votes. In a complete travesty of integrity, the board voted for Hayes by virtue of its Republican majority. Thus, Florida’s key electoral votes went to Hayes. The Republican Governor certified them with the official blessing of the state. The outraged Democrats held a meeting and had the Attorney General certify the Tilden electors. With this action, a new and dangerous complication entered the scene. Democrats, claiming dishonesty by the canvassing boards, were certifying their own electors by whatever legal or quasi-legal means they could. To further complicate matters, Florida Democrats elected G. F. Drew as Governor and he appointed a new board of canvassers who promptly judged Tilden’s electors to be victorious. In South Carolina, where Wade Hampton had been elected Governor, there were unqualified demands to disenfranchise the Hayes electors.

As a precaution, General Grant ordered Federal troops into all three state capitals, directing General Sherman ‘to see that the proper and legal boards of canvassers are unmolested in the performance of their duties’. That meant Hayes would win. At this point, Samuel Tilden’s followers almost begged him to denounce the plot publicly, but he would no nothing to prejudice the legal process. This is somewhat difficult to understand in view of his previous anti-fraud successes.

The Senate and House of Representatives convened for the second session of the 44th Congress on December 4th, 1876. It was just two days before the date set for Presidential electors chosen in each state to meet and declare their choice for President and Vice-President of the United States. It was the responsibility of each state Governor and Secretary of State to affix the official state seal to the voting certificates and send them to the President of the Senate in Washington D.C. who would then count them before a joint session of Congress.

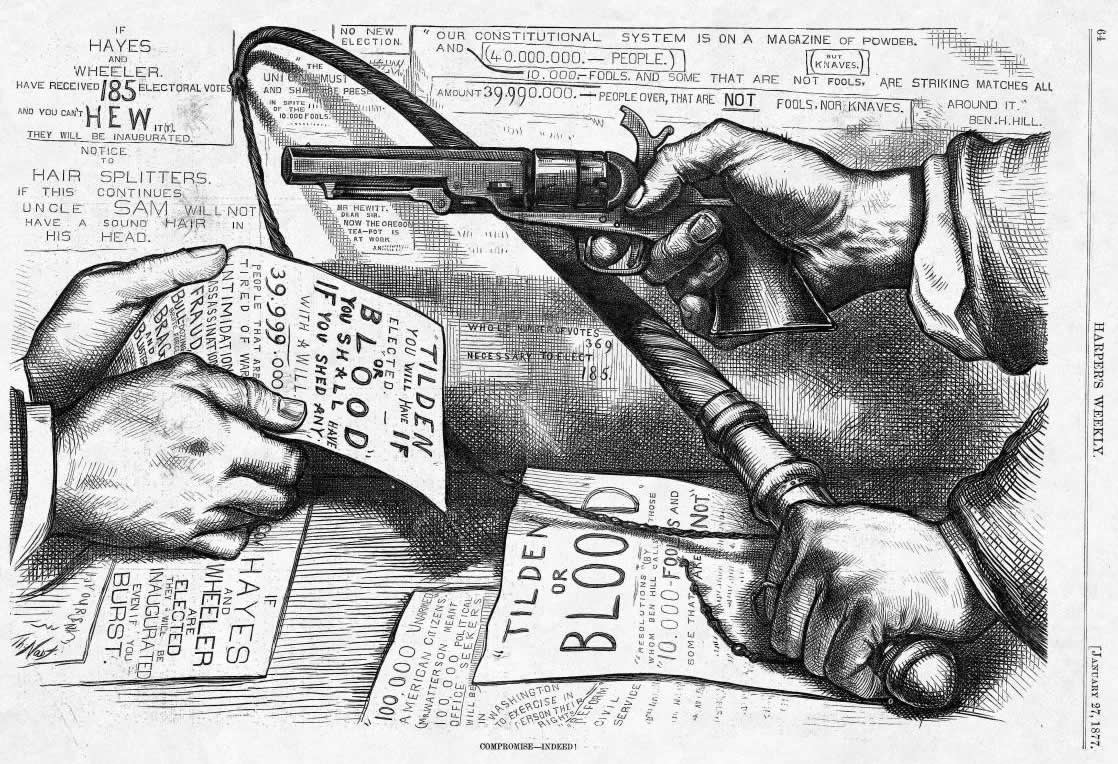

Since the Senate was controlled by Republicans, the Democratic House demanded the right to decide which votes were valid. The Senate, understandably, refused. Here was an incredible situation; each day bringing the United States closer to March 4th, the date when Grant’s term expired. Who would succeed him and how would it be done? Rumblings of a new civil war rolled ominously across America. There were drills and parades and wartime units began to reform. Even cool heads discussed the possibility of the National Guard, under the command of Democratic Governors in most states, marching on Washington to install Tilden by force, if necessary. In that case, the Regular Army under Grant would oppose the Guard as Hayes had been ‘legally’ elected.

It was an unthinkable prospect. Fortunately, there were men of influence on both sides who saw that a peaceful solution was absolutely mandatory. On December 14th, the House appointed a committee to approach the Senate in the hope that a tribunal could be created; one ‘whose authority none can question and whose decision all will accept as final’. After much debate, an Electoral Commission was approved. Congress proceeded to set up a group of 15 men; five from the Senate, five from the House and five from the Supreme Court. Presumably, the Court Justices would be non-partisan. Both Hayes and Tilden declared the Commission unconstitutional, but they reluctantly agreed to accept its verdict.

It was an unthinkable prospect. Fortunately, there were men of influence on both sides who saw that a peaceful solution was absolutely mandatory. On December 14th, the House appointed a committee to approach the Senate in the hope that a tribunal could be created; one ‘whose authority none can question and whose decision all will accept as final’. After much debate, an Electoral Commission was approved. Congress proceeded to set up a group of 15 men; five from the Senate, five from the House and five from the Supreme Court. Presumably, the Court Justices would be non-partisan. Both Hayes and Tilden declared the Commission unconstitutional, but they reluctantly agreed to accept its verdict.

It was clear to everyone what would happen without the Commission. Republican Senator Thomas Ferry of Michigan, presiding officer of the Senate, would open the certificates before a joint session and declare Hayes the winner by 185 to 184 electoral votes. The House would then immediately adjourn to its own chambers where Speaker Samuel Randall would declare no electoral majority and throw the election into a vote by each state delegation in the House. That would assure Tilden’s victory, and on March 4th, 1877 both Hayes and Tilden would be in Washington to be inaugurated as President of the United States. Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York described this route as a ‘Hell-gate paved and honeycombed with dynamite’. It was no understatement.

The Commission held its first session just four weeks before the inauguration. Democratic members of the Commission pressed for a searching examination of the honesty of the canvassing boards. The Republican members claimed that the legal state authorities had filed legitimate certificates and Congress had no power to interfere.

The Commission finally voted along party lines with the decision going to Hayes, 8 to 7. On Friday, March 2nd at 4am, the Senate awarded the last certificate to Hayes. It was just two days before the inauguration. The fury of the South was matched by its Democratic allies in the North. All eyes turned to Samuel J. Tilden. If he claimed that the will of the American people had been frustrated by partisan duplicity and fraud, then America faced civil war. Instead, Tilden said: ‘It is what I expected.’

Electoral map of 1876: Republican wins in red, Democrat in blue, non-states in grey.

Open conflict might still have been a possibility except for a meeting that has since been the subject of much speculation. One week before the inauguration, Southern Democrats and Republicans met at the Wormley Hotel in Washington in an effort to find some compromise before it was too late. There is ample evidence to suggest that a quid pro quo was reached; the South to agree to Hayes’ election if the North would agree to abandon all efforts to maintain carpetbag regimes in the South. That meant withdrawal of Federal troops. In return, the South presumably agreed not to take reprisals against African-Americans or carpetbag officials.

For that matter, the South and its Democratic friends in the North already held a powerful sword over the head of the United States Army. They attached a clause to the Army Appropriations Bill that outlawed the use of Federal troops to sustain state governments in the South without Congressional approval. When the Senate refused the clause, the House simply adjourned and left the Army without funds to pay soldiers. Morale collapsed and the end of Reconstruction was at hand.

After the decision, Tilden commented: ‘I can retire to private life with the consciousness that I shall receive from posterity the credit for having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people, without any of the cares.’ That summer he sailed for Europe for a year’s vacation. Rutherford B. Hayes took the oath of office in private, kissing the open Bible at Psalm 118:13 ‘… the Lord helped me’.

There was no inaugural parade or ball. There was little to celebrate.

de gran parte de las colonias americanas, y posteriormente la inestabilidad política, que desangró al país social y económicamente.

de gran parte de las colonias americanas, y posteriormente la inestabilidad política, que desangró al país social y económicamente.

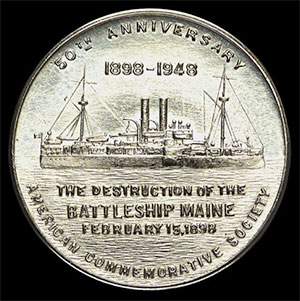

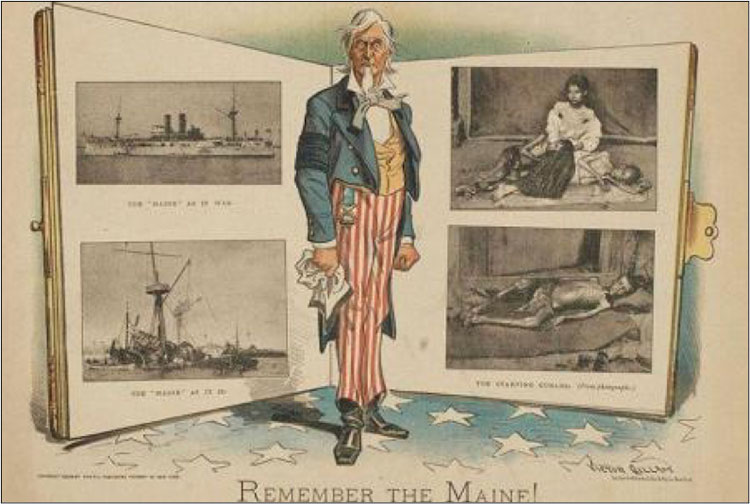

El gobierno de los Estados Unidos poco después del hundimiento ordenó la constitución de una comisión de investigación de la Armada, encabezada por el capitán William T Sampson. El gobernador español de Cuba, Ramón Blanco y Erenas había propuesto en su lugar una comisión conjunta hispano-estadounidense, Esta fue rechazada por el cónsul estadounidense en la isla.

El gobierno de los Estados Unidos poco después del hundimiento ordenó la constitución de una comisión de investigación de la Armada, encabezada por el capitán William T Sampson. El gobernador español de Cuba, Ramón Blanco y Erenas había propuesto en su lugar una comisión conjunta hispano-estadounidense, Esta fue rechazada por el cónsul estadounidense en la isla. Otra inconsistencia fue que solo hubo un testigo técnico, el comandante George Converse, de la base de torpederos de Newport en Rhode Island. El Capitán Sampson leyó al comandante Converse una situación hipotética, en la que un fuego en una carbonera hiciera entrar en ignición los almacenes de proyectiles de 152 mm, con el resultado de una explosión que hundiera el buque.

Otra inconsistencia fue que solo hubo un testigo técnico, el comandante George Converse, de la base de torpederos de Newport en Rhode Island. El Capitán Sampson leyó al comandante Converse una situación hipotética, en la que un fuego en una carbonera hiciera entrar en ignición los almacenes de proyectiles de 152 mm, con el resultado de una explosión que hundiera el buque. “En opinión del Tribunal, el Maine fue destruido por la explosión de una mina submarina que causó la explosión parcial de dos o más de sus almacenes de munición delanteros”. (7º hallazgo de la corte).

“En opinión del Tribunal, el Maine fue destruido por la explosión de una mina submarina que causó la explosión parcial de dos o más de sus almacenes de munición delanteros”. (7º hallazgo de la corte). A partir de diciembre del año 1910 se construyó una ataguía alrededor de los restos del naufragio y el agua fue bombeada fuera, dejando al descubierto los restos del naufragio a finales del año 1911.

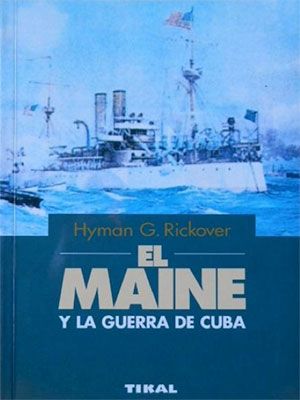

A partir de diciembre del año 1910 se construyó una ataguía alrededor de los restos del naufragio y el agua fue bombeada fuera, dejando al descubierto los restos del naufragio a finales del año 1911. El almirante Hyman Richover intrigado por el desastre, comenzó una investigación privada en el año 1974. Utilizando información de las dos comisiones oficiales, periódicos, documentación oficial e información sobre la construcción y municiones del Maine, llegó a la conclusión de que la explosión no estuvo causada por una mina.

El almirante Hyman Richover intrigado por el desastre, comenzó una investigación privada en el año 1974. Utilizando información de las dos comisiones oficiales, periódicos, documentación oficial e información sobre la construcción y municiones del Maine, llegó a la conclusión de que la explosión no estuvo causada por una mina.

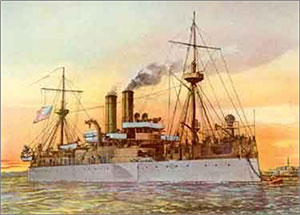

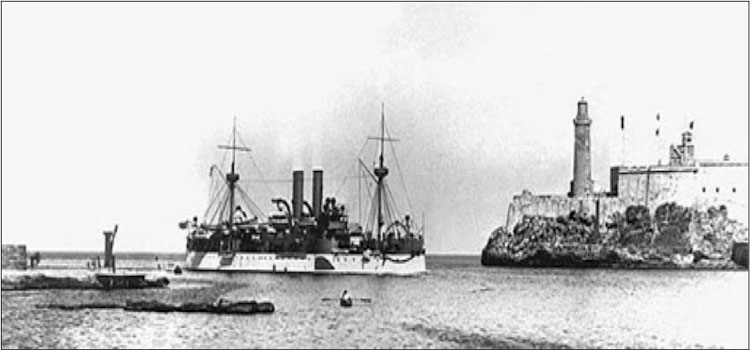

El Maine entrando en La Habana

El Maine entrando en La Habana El tratado de paz de París obligaba a España a renunciar a sus colonias americanas y Filipinas

El tratado de paz de París obligaba a España a renunciar a sus colonias americanas y Filipinas