Mañana 27 de mayo de 2023, Henry A. Kissinger cumplirá cien años de vida. Tal efemeride ha provocado una gran atención mediática y académica. Y no es para menos, pues Kissinger es una de las figuras más controversiales de la historia de Estados Unidos. Por ocho años dirigió la politica exterior estadounidense, primero como asesor de seguridad nacional de Nixon, y luego como Secretario de Estado de Ford. Sobrevivió inmacualado al escandalo de Watergate para convertirse en una figura venerada por muchos, que le consideran un gran hombre de Estado. Sin embargo, tras esa imagen se esconden sombras muy tenebrosas que llevan a muchos a denunciarle como uno de los peores criminales de guerra de la Historia. Quienes así le describen le acusan de ser responsable –directo o indirecto– de la muerte de millones personas. Entre las víctimas de su real politik y su maquiavelismo, destacan millones de camboyanos, masacrados durante cuatro años de bombardeos ilegales. Pero la lista es más extensa e incluye a vietnamitas, angoleños, chilenos, argentinos, timorenses, sahuaries y, especialmente, estadounidenses. A esto últimos los sacrificó alargando innecesariamente el conflicto indochino en el que la arrogancia imperial atrapó a Estados Unidos por más de dos décadas.

Uno de los analistas más críticos de la figura de Kissinger es el historiador Greg Grandin. En este artículo publicado en la revista The Nation, Grandin desmitifica la figura de Kissinger, recordándonos el triste papel que éste jugó saboteando un acuerdo de paz que pudo haber acabado con la guerra de Vietnam en 1968. Grandin también examina actuación de Kissinger en el proceso que culminó en el escándalo Watergate, cuestionando la idea generalizada de que el Secretario de Estado no tuvo nada que ver con los crímenes que llevaron a la destrucción de su jefe Richard M. Nixon.

Grandin nos retrata a Kissinger como un personaje siniestro y manipulador, dispuesto a todo por llegar y mantenerse en el poder.

El Dr. Grandin es profesor de historia en la Universidad de Yale y autor, entre otros trabajos, de Kissinger’s Shadow The Long Reach of America’s Most Controversial Statesman (McMillan, 2015).

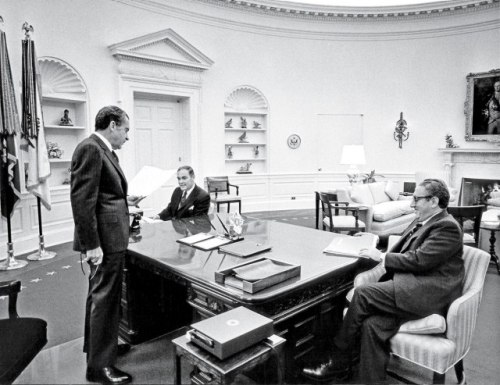

Richard M. Nixon, Henry Kissinger y el Coronel Alexander M. Haig Jr., 1972.

A sus 100 años Kissinger sigue si enfrentar la justicia

Greg Gradin

The Nation 25 de mayo de 2023

Henry Kissinger debería haber caído con el resto de ellos: Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell, Dean y Nixon. Sus huellas dactilares estaban por todo Watergate. Sin embargo, sobrevivió en gran medida manipulando a la prensa. Hasta 1968, Kissinger había sido Republicano del grupo de Nelson Rockefeller, aunque también se desempeñó como asesor del Departamento de Estado en la administración Johnson. Kissinger quedó atónito por la derrota de Rockefeller ante Richard Nixon en las primarias; según los periodistas Marvin y Bernard Kalb, “lloró”. Kissinger creía que Nixon era “el más peligroso, de todos los hombres que se postulaban a la presidencia”. Sin embargo, no pasó mucho tiempo antes de que Kissinger entrara en contacto con la gente de Nixon, ofreciendo usar sus contactos en la Casa Blanca de Johnson para filtrar información sobre las conversaciones de paz con Vietnam del Norte. Todavía profesor de Harvard, trató directamente con el asesor de política exterior de Nixon, Richard V. Allen, quien en una entrevista concedida al University of Virginia Miller Center dijo que Kissinger, “por su cuenta”, se ofreció a transmitir información que había recibido de un asistente que asistía a las conversaciones de paz. Allen describió a Kissinger como actuando muy de capa y espada, llamándolo desde teléfonos públicos y hablando en alemán para informar sobre lo que había sucedido durante las conversaciones.

A finales de octubre, Kissinger le informó a la campaña de Nixon: “En París están descorchando el champán”. Horas más tarde, el presidente Johnson suspendió los bombardeos. Un acuerdo de paz podría haber empujado la candidatura presidencial de Hubert Humphrey, quien se estaba acercando a Nixon en las encuestas, a la cima. La gente de Nixon actuó rápidamente: instaron a los vietnamitas del sur a descarrilar las conversaciones.

A través de escuchas telefónicas e interceptaciones, el presidente Johnson se enteró de que la campaña de Nixon le estaba diciendo a los vietnamitas del sur “que esperaran hasta después de las elecciones”. Si la Casa Blanca hubiera hecho pública esta información, la indignación pudo haber inclinado la elección a favor de Humphrey. Pero Johnson dudó. “Esto es traición”, dijo, citado en el excelente libro de Ken Hughes Chasing Shadows: The Nixon Tapes, the Chennault Affair, and the Origins of Watergate, “sacudiría al mundo”.

Johnson permaneció en silencio. Nixon ganó. La guerra continuó.

Esa October Surprise (sorpresa de octubre) inició una cadena de eventos que conducirían a la caída de Nixon. Kissinger, que había sido nombrado Asesor de Seguridad Nacional, aconsejó a Nixon que ordenara el bombardeo de Camboya para presionar a Hanoi a regresar a la mesa de negociaciones. Nixon y Kissinger estaban desesperados por reanudar las conversaciones que habían ayudado a sabotear, y su desesperación se manifestó en ferocidad. “’Salvaje’ era una palabra que se usaba una y otra vez” para discutir lo que había que hacer en el sudeste asiático, recordó uno de los ayudantes de Kissinger. Bombardear Camboya (un país con el que Estados Unidos no estaba en guerra), lo que eventualmente rompería el país y conduciría al surgimiento de los Jemeres Rojos, era ilegal. Así que tenía que hacerse en secreto. La presión para mantenerlo en secreto extendió la paranoia dentro de la administración, lo que llevó a Kissinger y Nixon a pedirle a J. Edgar Hoover que interviniera los teléfonos de los funcionarios de la administración. La filtración de los Papeles del Pentágono de Daniel Ellsberg hizo que Kissinger entrara en pánico. Temía que, dado que Ellsberg tenía acceso a los periódicos, también podría saber lo que Kissinger estaba haciendo en Camboya.

El lunes 14 de junio de 1971, el día después de que The New York Times publicara su primera historia sobre los Papeles del Pentágono, Kissinger explotó, gritando: “Esto destruirá totalmente la credibilidad estadounidense para siempre … Destruirá nuestra capacidad de conducir la política exterior con confianza. Ningún gobierno extranjero volverá a confiar en nosotros”.

“Sin el estímulo de Henry”, escribió John Ehrlichman en sus memorias, Witness to Power, “el presidente y el resto de nosotros podríamos haber llegado a la conclusión de que los documentos eran un problema de Lyndon Johnson, no nuestro”. Kissinger “avivó la llama de Richard Nixon al rojo vivo”.

¿Por qué? Kissinger acababa de comenzar las negociaciones para restablecer las relaciones con China y temía que el escándalo pudiera sabotearlas. Haciendo clave su actuación para despertar los resentimientos de Nixon, describió a Ellsberg como inteligente, subversivo, promiscuo, perverso y privilegiado: “Ahora se ha casado con una chica muy rica”, le dijo Kissinger a Nixon. Comenzaron a animarse mutuamente”, recordó Bob Haldeman (citado en la biografía de Kissinger de Walter Isaacson), “hasta que ambos estaban en un frenesí”. Si Ellsberg sale ileso, Kissinger le dijo a Nixon, “muestra que usted es un débil, señor presidente”, lo que llevó a Nixon a establecer los Plumbers (los Plomeros), la unidad clandestina que realizaba escuchas y robos, incluso en la sede del Comité Nacional Demócrata en el Complejo Watergate.

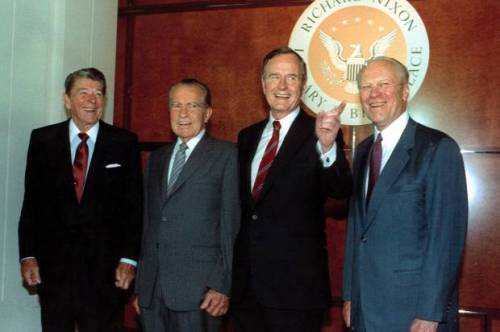

Rockefeller, Ford y Kissinger

Seymour Hersh, Bob Woodward y Carl Bernstein presentaron historias que apuntaban a Kissinger como parte de la primera ronda de escuchas telefónicas ilegales, establecidas por la Casa Blanca en la primavera de 1969 para mantener en secreto su bombardeo de Camboya.

Aterrizando en Austria de camino a Oriente Medio en junio de 1974 y descubriendo que la prensa había publicado más historias y editoriales poco halagadores sobre él, Kissinger celebró una conferencia de prensa improvisada y amenazó con renunciar. Fue a todas luces una fanfarronada. “Cuando se escriba el récord”, dijo, aparentemente al borde de las lágrimas, “se podrá recordar que tal vez se salvaron algunas vidas y tal vez algunas madres pueden descansar más tranquilas, pero eso se lo dejo a la historia. Lo que no dejaré a la historia es una discusión sobre mi honor público”.

El truco funcionó. “Parecía totalmente auténtico”, dijo la revista New York. Como si retrocedieran ante su propia tenacidad repentina al exponer los crímenes de Nixon, los reporteros y presentadores de noticias se unieron en torno a Kissinger. Mientras que el resto de la Casa Blanca se reveló como un grupo de matones, Kissinger siguió siendo alguien en quien Estados Unidos podía creer. “Estábamos medio convencidos de que nada estaba más allá de la capacidad de este hombre notable”, dijo Ted Koppel de ABC News en un documental de 1974, describiendo a Kissinger como “el hombre más admirado de Estados Unidos”. Era, agregó Koppel, “lo mejor que teníamos”.

Ahora sabemos mucho más sobre los otros crímenes de Kissinger, el inmenso sufrimiento que causó durante sus años como funcionario público. Dio luz verde a golpes de estado y permitió genocidios. Les dijo a los dictadores que hicieran sus asesinatos y torturas rápidamente, vendió a los kurdos y dirigió la operación fallida para secuestrar al general chileno Ren. Schneider (con la esperanza de descarrilar la toma de posesión del presidente Salvador Allende), que resultó en el asesinato de Schneider. Su giro posterior a Vietnam hacia el Medio Oriente dejó a esa región en caos, preparando el escenario para las crisis que continúan afligiendo a la humanidad.

Sin embargo, sabemos poco sobre lo que vino después, durante sus cuatro décadas de trabajo con Kissinger Associates. La “lista de clientes” de la firma ha sido uno de los documentos más buscados en Washington desde al menos 1989, cuando el senador Jesse Helms exigió sin éxito verla antes de considerar confirmar a Lawrence Eagleburger (un protegido y empleado de Kissinger Associates) como Subsecretario de Estado. Más tarde, Kissinger renunció como presidente de la Comisión 9/11 en lugar de entregar la lista para su revisión pública. Kissinger Associates fue uno de los primeros actores en la ola de privatizaciones que tuvo lugar después del final de la Guerra Fría, en la antigua Unión Soviética, Europa del Este y América Latina, ayudando a crear una nueva clase oligárquica internacional. Kissinger había utilizado los contactos que hizo como funcionario público para fundar una de las empresas más lucrativas del mundo. Luego, habiendo escapado de la mancha de Watergate, utilizó su reputación como sabio de la política exterior para influir en el debate público, en beneficio, podemos suponer, de sus clientes. Kissinger fue un entusiasta defensor de ambas Guerras del Golfo, y trabajó estrechamente con el presidente Clinton para impulsar el TLCAN a través del Congreso. La firma también hizo un libro sobre las políticas implementadas por Kissinger. En 1975, como secretario de Estado, Kissinger ayudó a Union Carbide a establecer su planta química en Bhopal, trabajando con el gobierno indio y asegurando fondos de los Estados Unidos. Después del desastre de la fuga química de la planta en 1984, Kissinger Associates representó a Union Carbide, negociando un miserable acuerdo extrajudicial para las víctimas de la fuga, que causó casi 4,000 muertes inmediatas y expuso a otro medio millón de personas a gases tóxicos. Hace unos años, mucha fanfarria asistió a la donación de Kissinger de sus documentos públicos a Yale. Pero nunca sabremos la mayor parte de lo que su empresa ha estado haciendo en Rusia, China, India, Medio Oriente y otros lugares. Se llevará esos secretos con él cuando se vaya.

Sin embargo, sabemos poco sobre lo que vino después, durante sus cuatro décadas de trabajo con Kissinger Associates. La “lista de clientes” de la firma ha sido uno de los documentos más buscados en Washington desde al menos 1989, cuando el senador Jesse Helms exigió sin éxito verla antes de considerar confirmar a Lawrence Eagleburger (un protegido y empleado de Kissinger Associates) como Subsecretario de Estado. Más tarde, Kissinger renunció como presidente de la Comisión 9/11 en lugar de entregar la lista para su revisión pública. Kissinger Associates fue uno de los primeros actores en la ola de privatizaciones que tuvo lugar después del final de la Guerra Fría, en la antigua Unión Soviética, Europa del Este y América Latina, ayudando a crear una nueva clase oligárquica internacional. Kissinger había utilizado los contactos que hizo como funcionario público para fundar una de las empresas más lucrativas del mundo. Luego, habiendo escapado de la mancha de Watergate, utilizó su reputación como sabio de la política exterior para influir en el debate público, en beneficio, podemos suponer, de sus clientes. Kissinger fue un entusiasta defensor de ambas Guerras del Golfo, y trabajó estrechamente con el presidente Clinton para impulsar el TLCAN a través del Congreso. La firma también hizo un libro sobre las políticas implementadas por Kissinger. En 1975, como secretario de Estado, Kissinger ayudó a Union Carbide a establecer su planta química en Bhopal, trabajando con el gobierno indio y asegurando fondos de los Estados Unidos. Después del desastre de la fuga química de la planta en 1984, Kissinger Associates representó a Union Carbide, negociando un miserable acuerdo extrajudicial para las víctimas de la fuga, que causó casi 4,000 muertes inmediatas y expuso a otro medio millón de personas a gases tóxicos. Hace unos años, mucha fanfarria asistió a la donación de Kissinger de sus documentos públicos a Yale. Pero nunca sabremos la mayor parte de lo que su empresa ha estado haciendo en Rusia, China, India, Medio Oriente y otros lugares. Se llevará esos secretos con él cuando se vaya.

Traducido por Norberto Barreto Velázquez

El actual proceso de residenciamiento del Presidente Donald J. Trump ha provocado una serie de interrogantes no sólo políticas, sino también históricas. Debe recordarse que en más de doscientos años de historia de la república estadounidense, esta es la tercera vez que un residente de la Casa Blanca es residenciado (el triste honor lo comparten Adrew Johnson y William J. (Bill) Clinton).

El actual proceso de residenciamiento del Presidente Donald J. Trump ha provocado una serie de interrogantes no sólo políticas, sino también históricas. Debe recordarse que en más de doscientos años de historia de la república estadounidense, esta es la tercera vez que un residente de la Casa Blanca es residenciado (el triste honor lo comparten Adrew Johnson y William J. (Bill) Clinton).