The Cartoon that Made People Scare to Go War in 1914

Charles F. Howlett

HNN May 1i, 2014

Historians, journalists, and leading political figures are now commemorating the one hundredth anniversary marking the beginning of World War 1. At the time of this tragic event it was called the Great War and would be referred to in history textbooks as such for a mere twenty-one years after its conclusion. Sadly, the world experienced another global conflict starting in 1939 and the Great War became World War 1.

At the time armed conflict began in August 1914, it was considered the Great War because it was total and its impact felt worldwide. Primarily, in the low countries of Western Europe and France fierce battles were waged marked by trench warfare so graphically depicted by German soldier Eric Remarque’s powerful work All Quiet on the Western Front and visually displayed in the 1939 movie of the same name starring American actor Lew Ayers; Ayers, by the way, though classified as a conscientious objector, served as my dad’s Army combat medic in the Philippines in 1944-45. Battles were also fought on the high seas, principally in the North Atlantic where the submarine came to symbolize a new twist to conventional warfare, abandoning all forms of civility with respect to terms of engagement. There were also large cannons capable of launching shells twenty-plus miles, mechanized tanks, battleships, which the Germans proudly referred to as dreadnoughts, and worst of all, mustard gas. Indeed, over the course of four years, Europe, America, and parts of the decaying Ottoman Empire were thrust into the worst war civilization had ever encountered. It was a game changer and by the time it was over, November 11, 1918, at least 8.5 million combatants were killed and many more wounded, untold numbers of civilians died, whole empires were destroyed, and societies were devastated by modern technological warfare. Physical, moral, and psychological shock reverberated throughout the European continent and elsewhere.

No one could have predicted how catastrophic it would be. But at the start of hostilities when Germany officially invaded Belgium on August 4, 1917, bringing Great Britain into the war on the side of France and Russia, a cartoonist by the name of John Tinney McCutcheon burst upon the scene in an effort to capture the realities of the time. He would not disappoint as his vivid imagination and poignant realism gave instant credibility to the popularity of wartime cartoons as a serious form of journalism. Indeed, other cartoonists such as J.N. Ding (Jay Norwood Darling), James Harrison “Hal” Donahey, and Edwin Marcus would follow suit as they, too, used their artistic talents to depict the costs of war.

But it was McCutcheon who got the ball rolling. He was certainly an interesting and dynamic person who loved the thrill of adventure; he went where the story was, regardless of the dangers involved. He was born on an Indiana farm in 1870, but destined to travel worldwide. At the age of sixteen he entered Purdue University, switching majors from mechanical engineering to industrial arts because he hated math. He chose wisely as his skills as a graphic artist would eventually garner him a Pulitzer Prize in 1931 for his cartoon, “A Wise Economist Asks a Question.” He worked for the Chicago Tribune for forty years, entertaining thousands of readers each day as his cartoons appeared on the front page just above the fold. But none would have as much long lasting impact as the one that was published on August 7, 1914.

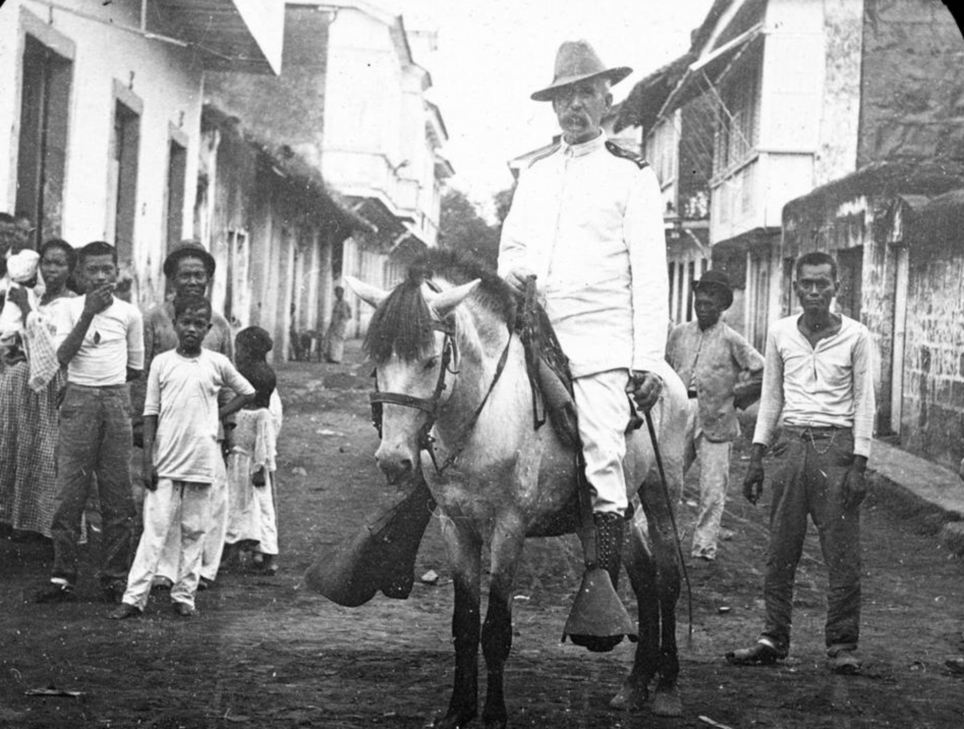

It was while he was working for the Chicago Tribune covering the political turmoil in Mexico, where he also met Pancho Villa and drew a cartoon of this Mexican revolutionary sitting at a table with a pistol laying on top, that war officially broke out in Europe. McCutcheon, the adventurer, promptly left Mexico for Chicago to obtain correspondent credentials. While awaiting a ship bound for England to cover the hostilities—he was one of only four American newspapermen to be on-the-scene reporters at the war’s beginning and would make two others trips, one riding in a French warplane that was shot at by the Germans—he sketched five noted war cartoons capturing his feelings about the European conflict. One stood out. He succinctly titled it “The Colors.”

The cartoon quickly captured the attention of a wide readership not only among Tribune subscribers but also among readers throughout the country. His cartoon was widely distributed and supporters of peace relied upon it to call attention to the dangers of war. Peace activists were moved by the depictions of McCutcheon’s cartoon. It provided anti-preparedness advocates with a simple, yet powerful, message that the burden of war is shouldered by all. “The Colors” also inspired a later effort by the newly-established Woman’s Peace Party to display its own “War Against War” exhibit, replete with peace/antiwar cartoons, attracting thousands of visitors in May 1916 in cities across the United States. In 1919, moreover, when George J. Hecht published his The War in Cartoons: A History of the War in 100 cartoons by 27 of the most prominent American Cartoonists, he promptly took notice of McCutcheon’s “The Colors.” It remains one of the most famous antiwar cartoons of all time.

When it first appeared no one, not even McCutcheon, could have guessed how influential it would become. But at the top of the first page in The Chicago Tribune on August 7, readers were instantaneously focused on a simple, yet compelling, cartoon with four panels. As readers gazed at each panel they were suddenly drawn to the words below each one: “Gold and green are the fields in peace”; “Red are the fields in war”; “Black are the fields when the cannons cease”; “And white forevermore.”

Each line takes on even greater significance when attached to the picture above. Readers are first drawn to a harvest of peaceful abundance as a farmer tills his soil while bundling his wheat. Then reality sets in as the field is littered with dead soldiers and smoke billowing upward from exploding cannon shells. In the aftermath of the battle are the mourners, grieving at the loss of so many innocent lives. Finally, one is led to white gravestones marking the place where the soldiers died. All the while three of four trees remain intact—nothing goes unscathed from war’s wrath—as witness to the tragic events that just took place, yet symbols of survival and future hope. Civilization must press on. His words, coupled with such powerful images, highlight the somber significance of war’s real impact on life.

And so, we have “The Colors.”

One hundred years later as we reflect on McCutcheon’s words and images in “The Colors,” we should be reminded, as the eminent peace historian Lawrence Wittner points out, that in the past century wars led to the deaths of over a hundred million people, and today, we live in a world armed with some 17,000 nuclear weapons. Many additional lives continue to be lost in the present century due to ongoing internal fighting and external war. Sadly, “the colors” haven’t changed.

This is the black and white version readers saw in the Chicago Tribune: