The new issue of Jacobin, commemorating the 150th anniversary of Union victory and emancipation, is out now.

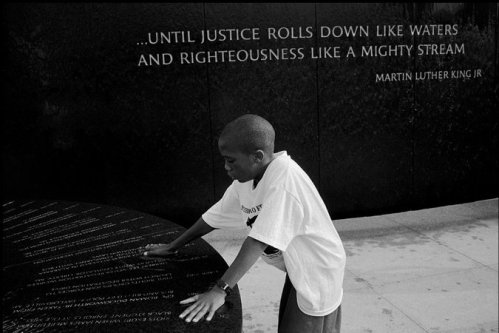

When black progressives today think about the Civil War, they are often more struck by what didn’t happen than what did.

Michelle Alexander’s much-lauded The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness is a case in point. Citing W. E. B. Du Bois’s lament that “former slaves had ‘a brief moment in the sun’ before they were returned to a status akin to slavery,” Alexander intimates that abolitionists failed to see that slavery was just one instance in a series of forms of “racialized social control” that not only have reappeared, but have also “evolved” and “become perfected, arguably more resilient to challenge, and thus capable of enduring for generations to come.”

What this narrative of unremitting bleakness overlooks is that the South chose armed rebellion in order to maintain political control over its system of labor — a system that enslaved blacks while impoverishing white agricultural and industrial laborers. From the standpoint of Southern planters and industrialists, the most terrifying prospect of emancipation was the possibility that laborers, black and white, would eschew elite guidance and wield political power in the form of the ballot and office-holding to further their own interests.

It came as no surprise, then, that when former slaves did begin to make this prospect a reality, Southern elites responded not only with violence and political fraud, but also with an intellectual campaign carried out in newspapers, journals, fiction, poetry, and historical writing to demonstrate the incapacity of blacks for self-government and the corruption that would ensue when the unlettered and inexperienced held the reins of power.

What is more surprising, if lesser known, is the role that many black elites (along with their sympathetic white counterparts) played in ratifying aspects of white reactionary thought toward the end of the nineteenth century. Some twenty-five years after Appomattox the fact that black men and unpropertied whites could vote made possible the rise of the Populist Movement, which directly challenged the economic order of the South by “proposing to substitute popular rule for the rule of capital.”

Black elites, whose political viability depended on their perceived legitimacy as “race leaders,” were disturbed by the reality of poor blacks acting politically without their guidance or sanction. And when the planter and industrial elite struck back against Populism with violence and disfranchisement — a backlash that tended to make all blacks, and not merely workers, its target — black elites sought to meliorate these effects by proposing a transformation — not of the economic basis of society, but rather of the black image in the white mind — to improve “race relations.”

Indeed for nearly 130 years, black elites in the United States have been offering up improved “race relations” rather then interracial workers alliances against capital as the primary solution to American inequality.

From the moment the Civil War ended, the question of what an American society without slavery would look like dominated political discussion. If the inaugural issue of the Nation magazine opined that“Nobody whose opinion is of any consequence, maintains any longer that [blacks’] claim to political equality is not a sound one,” the actual picture was more complicated.

While many black commentators and freedmen expected emancipation to usher black Americans fully and without restriction into the nation’s civic, social, and economic life, relatively few white Americans — even among those who abhorred slavery and championed the freedman’s political rights — felt similarly.

And while many Americans, black and white, celebrated the idea that the freedmen would now be able to join the ranks of wage laborers, few of either race saw this change as a significant step towards enhancing the political and economic power of workers generally against employers and landowners in the immediate aftermath of the war.

Recent commentary on the limits of emancipation has typically made much of the lack of racial egalitarianism within the Republican Party and even among abolitionists, seeing within this the seeds of subsequent political defeats.

On this account what made the Civil War and the Civil Rights victories of the 1960s something like “non-events” (and what could likewise undermine any success at ending mass incarceration) was the failure to, as Michelle Alexander puts it, “address . . . racial divisions and resentments,” which thereby allowed the next “system of racialized social control [to] emerge.”

In bringing slavery to an end the Civil War opened up contestation not only over the place that former slaves would have in American society, but also over the role that wage earners and women would play in a post-slavery political order.

Egalitarian visions, however, were met by concerted forces that did not want the end of slavery to lead to the complete emancipation of wage laborers. That is, any newly won freedoms should not address the way that market coercion severely limited the capacity of working Americans to control their lives and destinies. And while this limitation would ultimately prove equally consequential for the subsequent history of social justice, it has often been hidden by the significant shadow cast by the narrative of American racism and white supremacy.

When John William De Forest, a former Union officer and Freedman’s Bureau administrator, published his 1867 novel Miss Ravenal’s Conversion from Secession to Loyalty — which is perhaps the only significant novel about the Civil War written by an actual combatant — he sought, among other things, to champion a view that the “victory of the North is at bottom the triumph of laboring men living by their own industry, over non-laboring men who wanted to live by the industry of others.”

Steeped in the free labor ideology of the North, De Forest’s novel spliced a love story onto a realist account of the war in a way that reflected even as it sought to suppress tensions within the idea of free labor that had come to mark the difference between North and South.

In finally uniting the book’s hero Captain Edward Colburne of the Union army with erstwhile Southern sympathizer, Miss Lillie Ravenal, whom he has loved from the beginning of the novel, De Forest reveals that his view of the ideal free laborer was less the “propertyless proletarian” whose “freedom derived not from the ownership of productive property but from the unfettered sale of . . . labor power — itself a commodity — in a competitive market” than the “independent proprietor,” who had long been identified as being independent enough to secure the freedom of thought and action necessary for responsible citizenship.

We can see the inadequacy of wage labor in Colburne’s assessment of his economic situation after the war. Here we learn that “his salary as captain” had enabled him “to lay up next to nothing,” and that rising gold prices had diminished “the cash value” of what salary he did earn.

These dire prospects, however, do not turn out to be ultimately damning. Trained as a lawyer and in possession of a small inheritance from his dead father, Colburne, by partnering with a colleague, is able in short order to find himself “in possession of a promising if not an opulent business” and is ready to assume his role as head of household with the widowed Lillie Ravenal as his wife and her son as his stepson.

As the novel moves toward a full elaboration of its vision of free labor, it also leaves by the wayside the attempt by Lillie’s father, Dr Ravenal, to reconstruct black labor. Despite being born in South Carolina and having resided in New Orleans for twenty years, Dr Ravenal is a staunch Union man. At a moment when it appears that the Union forces have secured the area around New Orleans, Dr Ravenal determines to demonstrate the superiority of free labor to slave labor by eagerly taking charge of a plantation leased to him by the federal government. His responsibility, as he sees it, is not only economic, but also ideological and pedagogical. To be successful he must “produce not only a crop of corn and potatoes, but a race of intelligent, industrious and virtuous laborers.”

So, with lectures to the ex-slaves about the virtue of labor, sobriety, and the like, Dr Ravenal sets out to put black labor to work for wages. A Confederate counterattack cuts short his “grand experiment of freedman’s labor,” but not before the novel has had time enough to make clear its view that while reconstructing black labor may ultimately succeed, the effort will take time because the habits and attitudes ingrained by a history of enslavement will not disappear overnight.

Contrasting the realities of the South as he sees it to the “pure fiction” of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom, Dr Ravenal asserts, “There never was such a slave, and there never will be. A man educated under the degrading influences of bondage must always have some taint of uncommon grossness and lowness.” De Forest reiterated this vision in his reflections on his experience with Reconstruction in South Carolina, observing that “the Negro’s acquisition of property, and of those qualities which command the industry of others, will be slow. What better could be expected of a serf so lately manumitted?”

Undergirding De Forest’s vision of black freedmen gradually acquiring the skills and habits necessary to become prosperous cooperative laborers is what Eric Foner terms free labor’s belief that “a harmony of interests” defined the relation of capital to labor. The conditions necessary for capital to profit from its outlays were deemed to be those that were most conducive to the flourishing of labor. Class conflict could be imagined only in terms of deficiencies of character among the uncooperative.

Thus, despite their sympathies for the freedmen, black and white elites in the North generally embraced a view of the recently emancipated as a population in need of tutelage and leadership rather than as peers who had the capacity to present their own visions of social and economic life.

Black novelist, former abolitionist, and temperance advocate Frances E. W. Harper begins her 1892 novel, Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted, with depictions of illiterate and semi-literate black slaves debating among themselves the best course of action to take in response to the approaching Union army.

However, by the later chapters of that novel, as she seeks to validate genteel black leadership, a less flattering view of freed people emerges. In one instance Harper has one of her exemplary black characters respond to a claim in the newspaper that “colored women were becoming unfit to be servants for white people,” by concluding “that if they are not fit to be servants for white people, they are unfit to be mothers to their own children.”

This character’s readiness to interpret the uncooperativeness of black domestics as indication of debility is of a piece with the novel’s larger attempt to present black labor as educable and not rebellious. As we learn from another of the novel’s admirable characters, “the Negro is not plotting in beer-salons against the peace and order of society. His fingers are not dripping with dynamite, neither is he spitting upon your flag, nor flaunting the red banner of anarchy in your face.”

These sentiments were echoed by black social reformer, Anna Julia Cooper, in her landmark 1892 work of cultural commentary, A Voice From the South, which famously asserted that it would only be when the black woman was able to enter into American society on terms of equality that true social justice would be achieved. While on Cooper’s account genteel black women should expect acceptance as full equals, laboring blacks were to be prized for racial qualities that guaranteed their capacity as tractable workers.

Cooper writes that the Negro’s “Instinct for law and order, his inborn respect for authority, his inaptitude for rioting and anarchy, his gentleness and cheerfulness as a laborer, and his deep-rooted faith in God will prove indispensable and invaluable elements in a nation menaced as America is by anarchy, socialism, communism, and skepticism poured in with all the jail birds from the continents of Europe and Asia.”

To be sure black workers were not often met with open arms by their white counterparts. And it was not always the case that black novelists assumed innate antagonism between black and white laborers. J. McHenry Jones’s 1896 novel, Hearts of Gold, depicts Welsh miners in a Southern town who, moved by their sense that convict labor “degraded” labor generally and by “a deep-seated hatred . . . against systematic cruelty,” harbor a black runaway from a convict labor camp and then march en masse to destroy the camp and liberate its inmates.

Nonetheless, the representational tendency to align black Southern labor with the interests of their employers also reflected the continued commitment of black elites to the idea “that a community of equal men could be created by allying labor (blacks) and capital to produce material progress and enlightenment,” rather than by allying black laborers with their white counterparts. Instead of building the political power of labor, they called for building the integrity and esteem of the black race.

But whether these representations of black and white labor were disparaging or laudatory, what connected them was that they were, in some way or another, a response to the rise of the Southern Alliance in the 1880s, which was followed by the emergence of the Populist Party in the 1890s.

More to the point, according to Judith Stein, the Southern Alliance was paralleled by and helped fuel the Colored Farmers Alliance, which grew to encompass more than a million black farmers by the early 1890s. While in many cases the political organization of black farm laborers strengthened the hand of black political elites in seeking concessions from white industrialists and landowners, the efficacy of these alliances also challenged the ability of these elites to set the terms and goals of black political activity.

Black elites had sought to assure whites in both the South and the North that black political participation was consistent with the idea of rule by the “best” men of society. In principle then, if not always in fact, the stance of black political elites placed them at odds with the idea that relatively uneducated laborers could wield political power effectively. Thus, in novel after novel produced by the black political class, writers inserted scenes where unschooled black laborers pleaded for the leadership and guidance of their black genteel betters.

Of course, the most egregious disparager of interracial labor alliances against capital was Booker T. Washington, the founder of the Tuskegee Institute. Indeed, historian Michael Rudolph West has credited Washington with inventing “race relations.” Washington’s 1901 autobiography, Up From Slavery, attributed Southern labor unrest to the interference of “professional labour agitators” who had their eyes on the savings of thrifty workers and goaded them into going out on strikes that would leave them “worse off at the end.”

Washington’s rise as a political force in the South coincided with the rise of Populism. The ability of Populists to mount successful political challenges to Southern Democrats depended on the votes of black Alliance members.

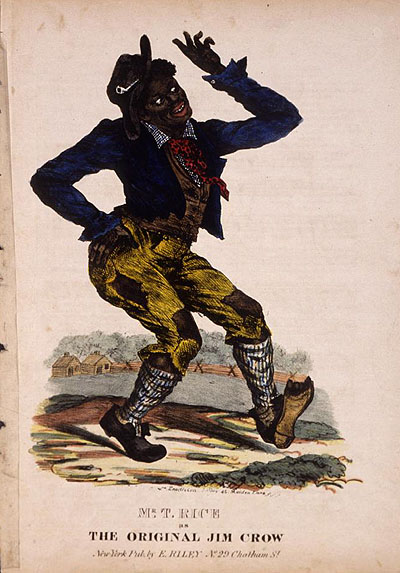

It was their awareness of this fact that drove white industrialists and planters in the 1890s to secure the dominance of the Democratic Party by pursuing across-the-board disfranchisement of blacks as well as many poor whites. Jim Crow America was the result of a successful counterrevolution against an interracial labor threat — a counterrevolution aided and abetted by the rise of Bookerism and the Tuskegee Machine.

What Tuskegee represented as an institution, and what Up From Slavery testified to as a program, was the idea that the problem of the South was not primarily a problem of who held political power, but rather one of determining how best to incorporate a despised caste into the social and economic fabric of the nation. In the place of political transformation Washington offered up race relations, with Tuskegee positioned to provide an army of “trained men and women to confront the militancy of an industrial proletariat.”

Viewed against the rise of Populism one can see that the Civil War, by granting blacks political rights, set the stage for what would become one of the most profound challenges to capital in the history of the United States. That the Populist challenge was defeated does not diminish its significance. And given that it was only after the defeat of Populism that disfranchisement and Jim Crow were able to succeed suggests the potential instructiveness of that history for the present moment, a history that does not attest simply to the periodic reemergence of white supremacy across time as Alexander and so many others have alleged.

Rather, if racialized forms of exclusion tend to rise in the wake of successful efforts by industrial and financial interests to undermine the political power of labor, to make our primary task that of addressing “racial divisions and resentments,” as Alexander calls for, risks giving pride of place to a new era of race relations, and not the broader vision of social justice that she describes at the end of The New Jim Crow.

Then, as now, the most reliable path to a progressive politics that produces true justice and human rights is that which begins with building the political power of workers. It is this proposition that has often made elite opponents of white supremacy — both black and white — deeply uncomfortable.

La década de 1920 trajo la segunda ola del Ku Klux Klan a las comunidades de todo el país. En el sur de la Florida, el Ku Klux Klan atacó a miembros de la comunidad cubana, en particular a aquellos que cruzaban la línea divisoria cada vez más sólida que separaba a mujeres y hombres, blancos y negros.

La década de 1920 trajo la segunda ola del Ku Klux Klan a las comunidades de todo el país. En el sur de la Florida, el Ku Klux Klan atacó a miembros de la comunidad cubana, en particular a aquellos que cruzaban la línea divisoria cada vez más sólida que separaba a mujeres y hombres, blancos y negros.

Dos años más tarde, en Manhattan, el gerente del New York Theatre llamó a la policía para denunciar al Sr. y la Sra. Roberts cuando se negaron a abandonar la sección de la orquesta para ir al balcón. A pesar del hecho de que sus boletos eran exactamente para donde estaban sentados y las leyes de derechos civiles del estado ciertamente estaban de su lado, el oficial de policía los amenazó con arrestarlos si no se movían. En un caso similar, unos años más tarde, en Cincinnati, Ohio, el hijo de un pastor local fue expulsado a la fuerza de un teatro por un oficial de policía porque la gerencia se opuso a su presencia en el establecimiento solo para blancos. Cuando el pastor acudió al alcalde y a la policía para quejarse de esta forma de discriminación descaradamente obvia, el oficial alegó ignorancia de la ley. Explicó que simplemente no era consciente de lo que no podía hacer como oficial. En otros casos, como en Filadelfia en 1929 y de nuevo en Muncie, Indiana, en 1934, el florete de Metcalfe se desarrolló exactamente como lo había planeado. Los clientes que insistían en sus derechos, negándose a moverse de los asientos comprados, fueron arrestados por conducta desordenada en el teatro.

Dos años más tarde, en Manhattan, el gerente del New York Theatre llamó a la policía para denunciar al Sr. y la Sra. Roberts cuando se negaron a abandonar la sección de la orquesta para ir al balcón. A pesar del hecho de que sus boletos eran exactamente para donde estaban sentados y las leyes de derechos civiles del estado ciertamente estaban de su lado, el oficial de policía los amenazó con arrestarlos si no se movían. En un caso similar, unos años más tarde, en Cincinnati, Ohio, el hijo de un pastor local fue expulsado a la fuerza de un teatro por un oficial de policía porque la gerencia se opuso a su presencia en el establecimiento solo para blancos. Cuando el pastor acudió al alcalde y a la policía para quejarse de esta forma de discriminación descaradamente obvia, el oficial alegó ignorancia de la ley. Explicó que simplemente no era consciente de lo que no podía hacer como oficial. En otros casos, como en Filadelfia en 1929 y de nuevo en Muncie, Indiana, en 1934, el florete de Metcalfe se desarrolló exactamente como lo había planeado. Los clientes que insistían en sus derechos, negándose a moverse de los asientos comprados, fueron arrestados por conducta desordenada en el teatro.