This Thanksgiving, it’s worth remembering that the narrative we hear about America’s founding is wrong. The country was built on genocide.

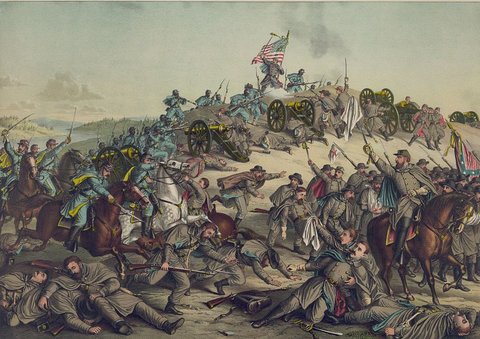

Massacre of American-Indian women and children in Idaho.

Under the crust of that portion of Earth called the United States of America — “from California . . . to the Gulf Stream waters” — are interred the bones, villages, fields, and sacred objects of American Indians. They cry out for their stories to be heard through their descendants who carry the memories of how the country was founded and how it came to be as it is today.

It should not have happened that the great civilizations of the Western Hemisphere, the very evidence of the Western Hemisphere, were wantonly destroyed, the gradual progress of humanity interrupted and set upon a path of greed and destruction. Choices were made that forged that path toward destruction of life itself—the moment in which we now live and die as our planet shrivels, overheated. To learn and know this history is both a necessity and a responsibility to the ancestors and descendants of all parties.

US policies and actions related to indigenous peoples, though often termed “racist” or “discriminatory,” are rarely depicted as what they are: classic cases of imperialism and a particular form of colonialism—settler colonialism. As anthropologist Patrick Wolfe writes, “The question of genocide is never far from discussions of settler colonialism. Land is life — or, at least, land is necessary for life.

The history of the United States is a history of settler colonialism — the founding of a state based on the ideology of white supremacy, the widespread practice of African slavery, and a policy of genocide and land theft. Those who seek history with an upbeat ending, a history of redemption and reconciliation, may look around and observe that such a conclusion is not visible, not even in utopian dreams of a better society.

That narrative is wrong or deficient, not in its facts, dates, or details but rather in its essence. Inherent in the myth we’ve been taught is an embrace of settler colonialism and genocide. The myth persists, not for a lack of free speech or poverty of information but rather for an absence of motivation to ask questions that challenge the core of the scripted narrative of the origin story.

Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” celebrates that the land belongs to everyone, reflecting the unconscious manifest destiny we live with. But the extension of the United States from sea to shining sea was the intention and design of the country’s founders.

“Free” land was the magnet that attracted European settlers. Many were slave owners who desired limitless land for lucrative cash crops. After the war for independence but before the US Constitution, the Continental Congress produced the Northwest Ordinance. This was the first law of the incipient republic, revealing the motive for those desiring independence. It was the blueprint for gobbling up the British-protected Indian Territory (“Ohio Country”) on the other side of the Appalachians and Alleghenies. Britain had made settlement there illegal with the Proclamation of 1763.

In 1801, President Jefferson aptly described the new settler-state’s intentions for horizontal and vertical continental expansion, stating, “However our present interests may restrain us within our own limits, it is impossible not to look forward to distant times, when our rapid multiplication will expand itself beyond those limits and cover the whole northern, if not the southern continent, with a people speaking the same language, governed in similar form by similar laws.”

Origin narratives form the vital core of a people’s unifying identity and of the values that guide them. In the United States, the founding and development of the Anglo-American settler-state involves a narrative about Puritan settlers who had a covenant with God to take the land. That part of the origin story is supported and reinforced by the Columbus myth and the “Doctrine of Discovery.”

The Columbus myth suggests that from US independence onward, colonial settlers saw themselves as part of a world system of colonization. “Columbia,” the poetic, Latinate name used in reference to the United States from its founding throughout the nineteenth century, was based on the name of Christopher Columbus.

The “Land of Columbus” was—and still is—represented by the image of a woman in sculptures and paintings, by institutions such as Columbia University, and by countless place names, including that of the national capital, the District of Columbia. The 1798 hymn “Hail, Columbia” was the early national anthem and is now used whenever the vice president of the United States makes a public appearance, and Columbus Day is still a federal holiday despite Columbus never having set foot on any territory ever claimed by the United States.

To say that the United States is a colonialist settler-state is not to make an accusation but rather to face historical reality. But indigenous nations, through resistance, have survived and bear witness to this history. The fundamental problem is the absence of the colonial framework.

Settler colonialism, as an institution or system, requires violence or the threat of violence to attain its goals. People do not hand over their land, resources, children, and futures without a fight, and that fight is met with violence. In employing the force necessary to accomplish its expansionist goals, a colonizing regime institutionalizes violence. The notion that settler-indigenous conflict is an inevitable product of cultural differences and misunderstandings, or that violence was committed equally by the colonized and the colonizer, blurs the nature of the historical processes. Euro-American colonialism had from its beginnings a genocidal tendency.

The term “genocide” was coined following the Shoah, or Holocaust, and its prohibition was enshrined in the United Nations convention adopted in 1948: the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

The convention is not retroactive but is applicable to US-indigenous relations since 1988, when the US Senate ratified it. The terms of the genocide convention are also useful tools for historical analysis of the effects of colonial- ism in any era. In the convention, any one of five acts is considered genocide if “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”:

- killing members of the group;

- causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life

- calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Settler colonialism is inherently genocidal in terms of the genocide convention. In the case of the British North American colonies and the United States, not only extermination and removal were practiced but also the disappearing of the prior existence of indigenous peoples—and this continues to be perpetuated in local histories.

Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) historian Jean O’Brien names this practice of writing Indians out of existence “firsting and lasting.” All over the continent, local histories, monuments, and signage narrate the story of first settlement: the founder(s), the first school, first dwelling, first everything, as if there had never been occupants who thrived in those places before Euro-Americans. On the other hand, the national narrative tells of “last” Indians or last tribes, such as “the last of the Mohicans,” “Ishi, the last Indian,” and End of the Trail, as a famous sculpture by James Earle Fraser is titled.

From the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River and south to the Gulf of Mexico lay one of the most fertile agricultural belts in the world, crisscrossed with great rivers. Naturally watered, teeming with plant and animal life, temperate in climate, the region was home to multiple agricultural nations. In the twelfth century, the Mississippi Valley region was marked by one enormous city-state, Cahokia, and several large ones built of earthen, stepped pyramids, much like those in Mexico. Cahokia supported a population of tens of thousands, larger than that of London during the same period.

Other architectural monuments were sculpted in the shape of gigantic birds, lizards, bears, alligators, and even a 1,330-foot-long serpent. These feats of monumental construction testify to the levels of civic and social organization. Called “mound builders” by European settlers, the people of this civilization had dispersed before the European invasion, but their influence had spread throughout the eastern half of the North American continent through cultural influence and trade.

What European colonizers found in the southeastern region of the continent were nations of villages with economies based on agriculture and corn the mainstay. This was the territory of the nations of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Choctaw and the Muskogee Creek and Seminole, along with the Natchez Nation in the western part, the Mississippi Valley region.

To the north, a remarkable federal state structure, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy — often referred to as the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy — was made up of the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk Nations and, from early in the nineteenth century, the Tuscaroras. This system incorporated six widely dispersed and unique nations of thousands of agricultural villages and hunting grounds from the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River to the Atlantic, and as far south as the Carolinas and inland to Pennsylvania.

The Haudenosaunee peoples avoided centralized power by means of a clan-village system of democracy based on collective stewardship of the land. Corn, the staple crop, was stored in granaries and distributed equitably in this matrilineal society by the clan mothers, the oldest women from every extended family. Many other nations flourished in the Great Lakes region where now the US-Canada border cuts through their realms. Among them, the Anishinaabe Nation (called by others Ojibwe and Chippewa) was the largest.

In the beginning, Anglo settlers organized irregular units to brutally attack and destroy unarmed indigenous women, children, and old people using unlimited violence in unrelenting attacks. During nearly two centuries of British colonization, generations of settlers, mostly farmers, gained experience as “Indian fighters” outside any organized military institution.

Anglo-French conflict may appear to have been the dominant factor of European colonization in North America during the eighteenth century, but while large regular armies fought over geopolitical goals in Europe, Anglo settlers in North America waged deadly irregular warfare against the indigenous communities.

The chief characteristic of irregular warfare is that of the extreme violence against civilians, in this case the tendency to seek the utter annihilation of the indigenous population. “In cases where a rough balance of power existed,” observes historian John Greniew, “and the Indians even appeared dominant—as was the situation in virtually every frontier war until the first decade of the 19th century—[settler] Americans were quick to turn to extravagant violence.”

Indeed, only after seventeenth- and early- eighteenth-century Americans made the first way of war a key to being a white American could later generations of ‘Indian haters,’ men like Andrew Jackson, turn the Indian wars into race wars.” By then, the indigenous peoples’ villages, farmlands, towns, and entire nations formed the only barrier to the settlers’ total freedom to acquire land and wealth. Settler colonialists again chose their own means of conquest. Such fighters are often viewed as courageous heroes, but killing the unarmed women, children, and old people and burning homes and fields involved neither courage nor sacrifice.

US history, as well as inherited indigenous trauma, cannot be understood without dealing with the genocide that the United States committed against indigenous peoples. From the colonial period through the founding of the United States and continuing in the twenty-first century, this has entailed torture, terror, sexual abuse, massacres, systematic military occupations, removals of indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories, and removals of indigenous children to military-like boarding schools.

Once in the hands of settlers, the land itself was no longer sacred, as it had been for the indigenous. Rather, it was private property, a commodity to be acquired and sold. Later, when Anglo-Americans had occupied the continent and urbanized much of it, this quest for land and the sanctity of private property were reduced to a lot with a house on it, and “the land” came to mean the country, the flag, the military, as in “the land of the free” of the national anthem, or Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land.”

Those who died fighting in foreign wars were said to have sacrificed their lives to protect “this land” that the old settlers had spilled blood to acquire. The blood spilled was largely indigenous.

Adapted from An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, out now from Beacon Press.

Read Full Post »