What General Holtzclaw Saw

By THOM BASSETT

The New York Times December 15, 2014

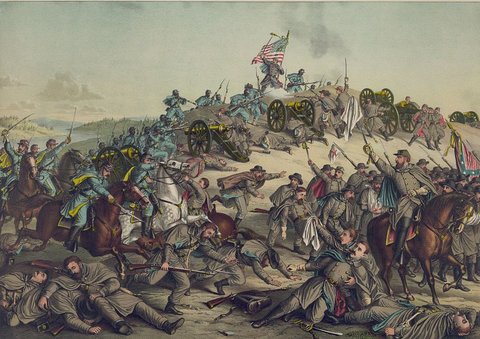

Viewed as a matter of tactics, the assault by the 13th United States Colored Troops against Confederates holding Overton Hill late on Dec. 16, 1864, contributed nothing to the Union victory at the Battle of Nashville. The Southerners easily repulsed the charge in a handful of minutes, leaving the regiment shot to pieces, its dead and wounded scattered across the muddy ground. In one sense, it was just another bloody and fruitless assay against strong defensive works, something that happened thousands of times in the Civil War.

Viewed as a matter of tactics, the assault by the 13th United States Colored Troops against Confederates holding Overton Hill late on Dec. 16, 1864, contributed nothing to the Union victory at the Battle of Nashville. The Southerners easily repulsed the charge in a handful of minutes, leaving the regiment shot to pieces, its dead and wounded scattered across the muddy ground. In one sense, it was just another bloody and fruitless assay against strong defensive works, something that happened thousands of times in the Civil War.

But something else, virtually unheard of in the war, also occurred as a result of this engagement. The African-American soldiers who charged Overton Hill not only earned the awed respect of white Union troops who witnessed their efforts; they also garnered heartfelt praise from an opposing Confederate general in his official report.

The first day of the Battle of Nashville, which commenced the final act of a desperate rebel campaign into Middle Tennessee, ended with Confederate Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Army of the Tennessee swept from its positions south of the city by a tide of Union forces. Rather than retreating completely from the field, though, Hood devoted the night of Dec. 15 to re-establishing a shortened defensive line across a range of hills southeast of Nashville. The right of Hood’s new emplacements was manned by Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee’s corps, whose line re-fused at the extreme right of its position atop Overton Hill (also known as Peach Orchard Hill).

Overton Hill was a strong anchoring point for Hood. It stood 300 feet high, with steep slopes. Federal troops hoping to drive off the Confederates would have to advance across open ground until they reached the hill, which was thick with underbrush and trees. About halfway up the hill the Confederates had downed trees to create further obstacles. Near the top they’d built breastworks with densely bunched abatis in front of them.

The Union Army failed to move quickly on the morning of Dec. 16 to exploit its victory the day before. By early afternoon, though, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Wood saw an opportunity as he arrayed his forces to the north and east of Overton Hill. It would be difficult to take the hill, but if it could be achieved the Federals could simultaneously cut off Hood’s only line of retreat and attack him from the rear. “The capture of half of the Rebel army would almost certainly [follow],” Wood wrote later, and so “the prize at stake was worth the hazard.”

By the time Wood was ready to attack, the unseasonably warm day had turned cold, and pelting rain fell on his men as they aligned themselves. Wood’s hastily improvised plan called for several regiments to attack simultaneously from different angles to offset the advantages of the Confederate position. Beginning around 2:45 p.m., Union forces slogged through a plowed field turned by the weather to heavy mud and then struggled up the hill.

The attack immediately became a Union disaster. Double canister shot from the hilltop tore into the advancing lines even before they reached the base of the hill. Some units misaligned as they moved forward and were enfiladed by the Confederates. Once the Northerners reached the lines of downed trees up the hill the advance was slowed even further, exposing them to murderous musket fire. The rebel defenses were so entangling, one Union officer reflected later, that his men were like flies caught in a spider’s web.

Wood’s forces soon retreated down the hill and across the churned field in wild disorder, with units dissolving in the destruction and panic. There were over a thousand Federal casualties, which represents almost a third of the total suffered by the Union Army in the entire two-day battle. “I have seen most of the battlefields of the West,” one Confederate would recall, “but never saw dead men thicker than in front of my [forces].”

At this point, with numerous Union regiments mauled and repulsed, the turn of the 13th U.S.C.T. was about to come. The regiment, which at Nashville consisted of merely 556 men and 20 officers, was created in September 1863. Its ranks were filled mainly with ex-slaves freed when Union forces occupied northern Tennessee in 1862. The 13th had principally guarded the rail lines that were gradually extended from the Nashville area to the south and east across the state. (These lines eventually would form the supply and communication basis Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman relied on to prepare for his assault on Georgia and the Carolinas.) On several occasions the unit defended the lines from rebel marauders. In late 1864 it was combined with two other black regiments to create the Second Colored Brigade and assigned to George H. Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland.

The Battle of Nashville was the 13th’s only full-scale combat of the war. As Confederate defenders were occupied by the first waves of the attack, the 13th moved into a position protected by brush at the base of the hill. After the main Union attack melted away under the blaze of the rebel rifles and cannon, the 13th rose with a thundering roar and, to the amazement of Federal and Confederate witnesses alike, ran for the summit of Overton Hill.

It was, as one commentator has put it, “a charge into hell itself.” The African-Americans, untried in fighting like this, assaulted a strongly defended hill in the face of fire, one Ohioan remembered, “such as veterans dread.” The 13th, unlike the other Union attackers, received no artillery support. Since the rest of the Union forces were broken up and scattered, the 13th was attacking by itself an entire corps placed securely behind breastworks and other defenses. As the former slaves and their white officers somehow came on and on, closer and closer to the top, the entire rebel line concentrated its slaughtering fire on them.

In minutes it was over. The regimental flag was lost to a Confederate trophy hunter after five color bearers had been shot down in succession. They were joined by 220 or so other officers and men — nearly 40 percent of the regiment’s fighting strength — who were killed or wounded in the brief attack.

Those who saw it were in awe of the 13th’s bravery. One Union officer wrote: “I never saw more heroic conduct showed on the field of battle than was exhibited by this body of men so recently slaves.” After the Confederate Army was routed by Union attacks that came from the other side of Hood’s line, a Yankee surgeon went to look where the 13th had attacked. “Don’t tell me negroes won’t fight!” he declared in a letter home. “I know better.”

Someone else who now knew better was the Confederate Brig. Gen. James T. Holtzclaw, whose men formed part of the defense on Overton Hill. In a January 1865 official report the Alabamian bore witness to the qualities displayed by the African-American soldiers. He wrote that they “made a most determined charge” and “gallantly dashed up to the abatis” only to be “killed by hundreds.” Holtzclaw also singled out the 13th’s officers for praise: “I noticed as many as three mounted who fell far in advance of their commands urging them forward.”

That Holtzclaw wrote these lines is remarkable, given the prevailing white Southern attitudes and practices toward African-American Union soldiers. Captured members of the U.S.C.T. were officially regarded by the Confederates as fomenting slave rebellion and faced death as punishment. At Fort Pillow the previous April, they were slaughtered en masse after Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s men captured them. African-American soldiers could also be sold into slavery or forced to work alongside slaves in support of the Confederate war effort.

Oddly, Union soldiers on the morning of Dec. 16 discovered that white comrades slain the day before had been stripped naked overnight by desperate Confederates in need of food, supplies and clothing, while the African-American dead were left untouched. Southern infantrymen, it seems, would rather go barefoot in winter than wear the shoes of a black man and go hungry instead of eating his hardtack.

There’s no evidence that Holtzclaw’s officially expressed admiration for the 13th U.S.C.T. reflected any racial progressivism on his part. The better explanation is this: A Southern general who fought in defense of a society built on slavery nevertheless saw, if only for a moment and dimly through the smoke and chaos of battle, the undeniable humanity of the men who charged his lines, willing to fight and die for freedom.

Follow Disunion at twitter.com/NYTcivilwar or join us on Facebook.

Sources: Wiley Sword, “The Confederacy’s Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, & Nashville”; The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies,” Vol. 45, Pt. 1.

Thom Bassett lives in Providence, R.I., and teaches at Bryant University. He is at work on a novel.