The Charleston Massacre and the Rape Myth of Reconstruction

We’re History June 22, 2015

As Dylann Roof massacred nine people in cold blood after they studied the Bible together on Wednesday night at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, he told a church member who survived that he felt compelled to carry out the murders. “You rape our women and you’re taking over our country,” Roof said. “And you have to go.” We might take such a bizarre statement as a sign that this act of racial terrorism was also the act of a lunatic. But if Dylann Roof is deranged, his derangement is deeply steeped in a history of white supremacy that has long expressed the threat of black economic and political power in sexual terms.

Apologists for slavery often contended that people of African descent were by nature bestial, and that they would surely revert to a state of savagery without the discipline of enslavement. These fears continued to haunt the white southern imagination through the era of emancipation and Reconstruction, as terrorist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan gained support from significant segments of the white southern populace in the late 1860s by claiming they acted as forces of law and order against hordes of black thieves and rapists intent on causing mayhem and despoiling white women. In truth, there were no waves of black crime during Reconstruction, and the Klan was little more than the paramilitary arm of the resurgent southern Democratic Party. The Klan existed to intimidate, brutalize, and murder economically ambitious and politically assertive black people and their allies, and its presence faded in the early 1870s as much because white Democrats had succeeded in retaking control of many southern state governments as because the federal government cracked down on the organization.

The unmistakable link between fears of black power and fears of the sexual violation of white women, however, not only outlasted Reconstruction but became an increasingly prominent element of white southern racial pathology as the nineteenth century progressed. Even the so-called Redemption of state governments by white Democrats could not entirely contain black political activism, and the chronically depressed southern economy produced masses of economically insecure white southerners who felt that black agricultural and industrial workers took too many of the region’s scarce resources, lacked proper deference to white people, and did just a bit too well for themselves. The widespread anxiety among white men that they would not be able to provide for their wives and children easily transformed into concerns that they would not be able to protect their wives and children. On the racially charged landscape of the post-emancipation South the logic of white supremacy called forth the violent response that it always did.

The phenomenon of lynching, which is America’s signature act of racial terror, began a noticeable rise in the 1880s and became epidemic by the turn of the twentieth century. And it was practically axiomatic in the minds of white southerners that such extralegal mob violence was necessary to clamp down on black sexual predators with designs on the bodies of white women. Even southern congressmen used such claims to defend lynchings. In the early 1920s, for example, Representative James Buchanan of Texas voiced his opposition to proposed federal anti-lynching legislation by denouncing “the damnable doctrine of social equality which excites the criminal sensualities of the criminal element of the Negro race and directly incites the diabolical crime of rape upon white women. Lynching follows as swift as lightning, and all the statutes of State and Nation cannot stop it.” Representative Thomas Upton Sisson of Mississippi agreed, asserting that white southern men “are going to protect our girls and womenfolk from these black brutes. When these black fiends keep their hands off the throats of the women of the South then lynching will stop.”

Such wildly racist delusions, not to mention the expressions of patriarchal control over white women, said far more about white men than they did about black men. Indeed, in light of the systematic rape of black women by white men dating back to the era of slavery, it takes no deep psychological insight to observe that the lurid horror of black rapists conjured by white southerners was more a matter of projection than of reality. The belief remained unshakable nonetheless, and those bold and courageous enough to observe that the threat of the black rapist was a myth placed themselves in tremendous danger. Most famously, when Tennessee journalist Ida B. Wells argued in the 1890s that most liaisons between white women and black men were consensual and that the specter of the black male rapist was a lie, a white mob destroyed the offices of her newspaper. Wells left the South altogether because she was sure she would be murdered.

The numbers of lynchings in the United States would eventually crest and then diminish over the course of the twentieth century, but the myth of the black rapist was a stubborn one to uproot. It was never far from the surface in white southern defenses of segregation during the Civil Rights Era, for instance, with the hostility to the prospect of integrated schools, swimming pools, and other public spaces often conveyed in terms of the idea that integration would mean “mongrelization,” as even black male children surely had their eyes on white girls. Wednesday’s attack in Charleston is plain evidence that the myth still thrives today, and that it is deadly.

What happened in Charleston is so rife with symbolism and so anchored in America’s racial past that it nearly leaves a person breathless. The shootings happened at a church that has long been the center of black activism in the state of South Carolina, in a city that was the heart of the mainland colonial transatlantic slave trade. That church is one that Denmark Vesey, who planned a thwarted slave rebellion, helped found in 1818, and that his son redesigned after whites burned the original building to the ground. The shootings happened one day after the 193rd anniversary of when Vesey’s rebellion would have transpired and two days before the Juneteenth holiday that commemorates the end of slavery in the United States. The shooter proudly placed a license plate on the front of his car bearing the Confederate battle flag that flew at full staff in front of the statehouse in Columbia even the day after the atrocity.

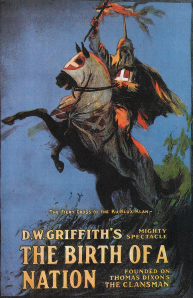

One smaller and perhaps less-observed symbolic element, however, may be the most telling. Dylann Roof was captured and arrested in the town of Shelby, North Carolina, which is the birthplace of author Thomas Dixon. Dixon’s most famous work, entitled The Clansman, glorifies the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan and imagines the organization as having saved the white South from a fusion of white abolitionist and black southern political rule and from legions of former slaves set on raping white women. Dixon’s book, published in 1905, was a vicious and mendacious act of distorted historical revisionism. But it was a powerful one. Ten years later it served as the source material for D.W. Griffith’s pathbreaking film The Birth of a Nation. The film places the attempted rape of a white woman by a former slave at the very core of the story, and it shows Klansmen as the saviors of white civilization from an oppressive government that is trying to forcibly impose black equality. The movie nearly singlehandedly prompted a national revival of the Ku Klux Klan. And it was a film that white audiences lined up for months to watch. That was true not only in the South. It was true everywhere in the United States. Fifty years after the Civil War ended, white Americans largely agreed that the nation born out of its ashes was one that rightfully belonged only to them.