Comparto este intetesante artículo sobre la criminalización de la música y los músicos afroamericanos. Su autora es la escritora Harmony Holiday, quien nos muestra como el racismo institucional de la sociedad estadounidense abarca básicamente todas las esferas, incluyendo la cultura popular. Holiday analiza como grandes estrellas de la música afroamericana como Billie Holiday, Thelonius Monk, Charles Mingus, y Miles Davis sufrieron persecucióny violencia policiaca por ser negros. La imagen de Billie Holliday muriendo esposada a su cama de hospital resulta demoledora. A otros como Abbey Licoln se les cerraron las puertas a clubs y casas disqueras.

Harmony Holiday Dreams of a Black Sound Unfettered

by White Desire

Literary Hub June 19, 2020

Billie Holiday died handcuffed to her hospital bed because her drug addiction had been criminalized. A Black FBI informant posed as a suitor, hunted her, fell in love with her even, and turned her in for heroin possession, not for hurting anyone, or violence, or for singing too beautiful and true a song but because she was self-medicating against the siege of being a famous Black woman in America, a woman who carried the weight of the nation’s entire soul in her music.

For as long as Black music has been popular, crossover, coveted by white listeners and dissected by white critics, it has also been criminalized by white police at all levels of law enforcement. A micro-archive of the criminalization of Black music and police presence within the music, focused on jazz music and improvised forms, shows why we now cry and chant unapologetically for abolition. Even when our life’s work is to bring more beauty into the world, to create new forms, we are brutalized, policed, jailed, and die in contractual or physical bondage. Or both.

Thelonius Monk’s composition In Walked Bud is dedicated to his friend, fellow pianist Bud Powell, a memento to the night when Bud protected Monk from police during a raid of the Savoy Ballroom in 1945. The Savoy was targeted as one of Black music’s epicenters in Harlem. Bud stepped between an officer and Monk and was struck in the head, incurring injuries that damaged his cognition, causing him to be institutionalized on and off for the rest of his life.

In 1951, Monk and Bud were sitting in a parked car when the NYPD narcotics division approached. Unbeknownst to Monk, Bud had a small stash of heroin and attempted to toss it out the window. It landed on Monk’s shoe instead—Monk was blamed, did not snitch on his friend, and was sent to Rikers Island for 60 days, held on $1,500 dollars bail. When released, Monk’s Cabaret Card, which granted him legal license to play in New York clubs, had been revoked. It would take years for the charges to be dropped and the license reinstated, years the Monk family and innovation in Black music suffered at the whims of the police. And the policing of Monk didn’t stop there.

In 1957, on a drive with Charlie Rouse and Nica, his rich white baroness friend, in Nica’s Bently, Monk asked to stop for a glass of water. Denied this simple request by the white waitress at the cafe they found, Monk just stood and stared at her, agape with disgust. The waitress called the police; when they arrived Monk walked right past them back into the car with Nica and Charlie. He would not get out when the police approached. Get out of the car you fucking nigger. Monk’s window was down and the officer started smashing his hands with a night stick: our genius Black pianist who gave us the break the space between Black thoughts and Black notes, getting his hands bashed and broken by police because he wanted a glass of water. Monk was cuffed, humming, his bloodied hands behind his back in chains.

Monk’s window was down and the officer started smashing his hands with a night stick: our genius Black pianist who gave us the break the space between Black thoughts and Black notes, getting his hands bashed and broken by police.

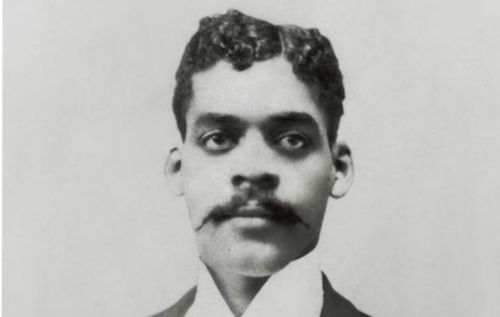

In 1959 Miles Davis was standing on the sidewalk outside of his own gig at Manhattan’s Birdland. He was with a white woman, smoking a cigarette between sets. A police officer pulled up and asked him what he was doing loitering—at that time a Black man just standing was criminalized, but especially one standing with a white woman. Miles pointed out his name on the marquee, explaining that he was between performances. This cavalier deference to the matter-of-fact seems to trigger the racism always-already seething in some cops.

Miles was beaten over the head with a nightstick, bloodied, cuffed, taken to jail. The incident was a legal nuisance and also altered his disposition, made him both more brooding and more volatile. In Miles’s case being policed in public life led to a rage he would only display in private, that he took out on his wives. His intimate relationships with Black women were overwhelmed by violence, he victimized them and beat into them deflected confessions of his feelings of powerlessness in the face of state violence. He could not be the father of “Cool” and a blatantly dejected Black man, so Black women became the symbols of a trouble he didn’t want to admit stemmed from white men, their policing, their scrutiny, and their over-familiar criticism.

Miles Davis in a New York courtroom, 1959.

Later in his life, when he lived in Malibu and drove expensive sports cars on its canyon roads, police would stop Miles routinely when he was on his way home, to interrogate him on the true owner of his car, had he stolen it, was he some white man’s driver, what was he doing in this white neighborhood with this expensive machine. Money, fame, all levels of success, were no exemption. Miles’s presence as a Black man was as policed by the state as his changing sound was by white music critics. Everyone wanted him as they saw him, in return he became so original that he could take his tone into almost any form, from painting to boxing, to screaming back at their prejudice on his horn, hexing detractors back into their formless obsessions with his immaculate Blackness.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5538719-1512856324-8745.jpeg.jpg)

In 1961, when the “Freedom Now!” Suite debuted, written by Max Roach and Oscar Brown, Jr., performed most visibly by Abbey Lincoln as she moaned and screamed its depiction of the path Black Americans took from slavery to citizenship, the result was the blacklisting of Max, Abbey, and Oscar from many performance venues in the US. The hushed accusations that they were controversial for making true music policed their ability to share that music with American audiences. Abbey screaming on stage like a fugitive slave found and being branded and beaten was a vision the country was not ready to allow without backlash.

Club owners and record companies helped marginalize their music, interrupted the course of star-making, and tamed some of the candid militancy in all of their spirits. The state can police Black music directly, but it can also deploy its tacit muzzle, which is almost worse for the anxiety and psychic distress it invites. These artists knew they were being surveilled and penalized for their expression but had no single name or entity to hold accountable, ensuring that some part of them blamed themselves and one another. Oscar Brown, Jr. even expressed resentment toward Max Roach for performing and releasing the suite at all, turning his reputation from benign griot to troublemaker in the eyes of the overseer owners of venues.

The fact that record companies and clubs and recording studios are owned primarily by white men adds another trapdoor to the labyrinth that polices Black music at every level. The boundaries between rehearsal and performance are skewed—with white men always watching and keeping time and signing the paychecks, the code switch isn’t flipped as often as it otherwise would be. There is always a stilted professionalism constraining the freest Black music when it’s recorded in white-owned studios or clubs—the music is not completely ours in those spaces. No matter how good we get at tuning out the white gaze its pressure is always immanent.

Hip hop’s most famous liberation chant is fuck the police. It’s been repeated so often it means almost nothing, it’s almost a call of endearment…

We feel this today in the music that jazz helped make way for. Hip hop, which began in Black neighborhoods as entirely ours, was colonized and coopted and policed into a popular form whose translation to white venues often reduces the music to sound and fury. What is the point of yelling about Black liberation to a bunch of white middle class college students, or at festivals where Black people aren’t even really comfortable or in attendance? What is the point of producing all this music to make white record executives richer and give them what they believe is a hood pass to obsess over and imitate Black forms.

Jazz begat hip hop, and we learned that our most militant sound was also our most commodifiable. The militancy was quickly overshadowed by criminalization, open-secret wars between Black rappers, public awareness of their rap sheets, of the personal business, all of that given to listeners who felt entitled, still do. Criminality became the vogue and Black criminality a fetish within hip hop, the parading of the rap sheet increasing desirability among white audiences who conflated crime with authenticity and realness, trouble glamorized and traded for clout. (When jazz musicians were criminalized it was more devastating, costing them their right to play.)

Prison and bondage have been effectively woven into Black acoustic consciousness. Policing and the police have become the most familiar chorus. Hip hop’s most famous liberation chant is fuck the police. It’s been repeated so often it means almost nothing, it’s almost a call of endearment, a calling forth of the police, a fuck you to them that implies they are omnipresent and within earshot all the time, ready to strike out against any Black song or singer who threatens their lurking fixation on Black life and Black sound.

As the musicians are policed and incriminated so too are their forms, so too is that thought that leads to new Black musical temperaments. Musicians who seek to remain true to themselves often self-marginalize, police their own public presence, reject fame and affiliation in order to keep from being ruined by it or policed into oblivion from the outside—and so fewer Black people hear them. Even still, the police ambush these private sects, asking why they’re at their gig or in response to a noise complaint, escalating to yet another incident, always haunting their music with some threat of captivity.

In the late 1960s jazz bassist Charles Mingus tried to open a jazz school in Harlem. He wanted a Black-owned and Black-run place, outside of the university, the studios, and clubs all owned by whites, to teach and develop the music. The city of New York kicked him out of the space, not for any real legal issues but because his wish was a threat to their embedded policing. They removed all of his belongings and arrested him, he cried in the back of the cop car as sheets of his music were left on the street to be swept away by the wind. No such school has been attempted since and Black music is developed and studied in heavily policed white westernized institutions or not at all.

My own father, a Black musician, was getting arrested the last time I saw him. He went to jail, he died. He had spent his life as a kind of warrior: he carried guns, he was the quickest draw anywhere, he mangled studio engineers or lawyers he felt were trying to rip him off, he could not read, had never been taught that skill, but he could kill if he had to. He was avenging something all the time, his vengeance was finally policed and criminalized, never rehabilitated in any more tender way, just returned as bondage. He sang songs in jail, entertained his jailers with stories and songs. I’m still avenging him. I’m still imagining his alter-destiny in a world where his very existence had not been criminalized.

In his story, “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” Henry Dumas, who himself was killed by police, invents a Blacks-only jazz club set in Harlem and an “afro-horn” that if heard by white people kills them. A group of white hipsters comes to the club one night, name drops, begs for entrance, and when they are denied repeatedly, they call on a police officer who forces the bouncer to let them in. They enter and start to absorb the music and before the first song is over they are dead, the frequency kills them. They were warned.

I dream of a Black music, a Black sound, free of the shackles of the white gaze, impossible for police to attack or scrutinize, ineffable to those forces, free even of white desire. Unbroken, lethal to detractors, wherein we can hear our unobstructed selves and get closer to them in other spheres of life, where the pleasure we derive from our music isn’t always fugitive, in escape from those forces that police it, and escaping us to reach or appease white audiences and white modes of consumption. I dream of the notes that only we can hear recovered, the ones multi-instrumentalist Rahsaan Roland Kirk called the missing Black notes that have been stolen and captured for years and years and years.

Harmony Holiday is a poet, dancer, archivist, mythscientist and the author of Negro League Baseball (Fence, 2011), Go Find Your Father/ A Famous Blues (Ricochet 2014) and Hollywood Forever (Fence, 2015). She was the winner of the 2013 Ruth Lily Fellowship and she curates the Afrosonics archive, a collection of rare and out-of print-lps highlighting work that joins jazz and literature through collective improvisation.

Read Full Post »

On August 28, 1963, as Martin Luther King Jr. gave his historic “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington, DC, these children sat in their cell bolstering their courage with freedom songs in solidarity with the thousands of marchers listening to Dr. King’s indelible speech on the National Mall. Soon after the March on Washington, during the same week of the bombing of the five little girls at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963, law enforcement released the Leesburg Stockade Girls and returned them to their families.

La presente obra analiza la evolución de la lucha y la resistencia de los afro-norteamericanos a lo largo de las décadas de 1970 y 1980 desde una perspectiva que incorpora las categorías de racismo, raza y clase. Desde la centralidad de las elaboraciones discursivas e institucionales de las nociones de raza y racismo, así como desde el papel fundamental que ha adquirido la ideología de la supremacía de la raza blanca en el devenir histórico estadounidense, la población negra ha entendido su lucha desde la noción de raza como lugar de resistencia, lo que ha delimitado sus acciones a la hora de perfilar estrategias de lucha colectiva. El estudio de determinados movimientos significativos de cada región del territorio (centro-oeste, el sur profundo, noreste, este) evidencia cómo estos permiten establecer conexiones y continuidades en cuanto a problemas, tácticas y estrategias, formas de organización, retóricas discursivas y tipos de participación, que dieron forma a un complejo, heterogéneo y versátil proceso de incesante movilización nacional mediante el cual la comunidad negra desafió al racismo institucional estadounidense bajo las consignas de raza y clase.

La presente obra analiza la evolución de la lucha y la resistencia de los afro-norteamericanos a lo largo de las décadas de 1970 y 1980 desde una perspectiva que incorpora las categorías de racismo, raza y clase. Desde la centralidad de las elaboraciones discursivas e institucionales de las nociones de raza y racismo, así como desde el papel fundamental que ha adquirido la ideología de la supremacía de la raza blanca en el devenir histórico estadounidense, la población negra ha entendido su lucha desde la noción de raza como lugar de resistencia, lo que ha delimitado sus acciones a la hora de perfilar estrategias de lucha colectiva. El estudio de determinados movimientos significativos de cada región del territorio (centro-oeste, el sur profundo, noreste, este) evidencia cómo estos permiten establecer conexiones y continuidades en cuanto a problemas, tácticas y estrategias, formas de organización, retóricas discursivas y tipos de participación, que dieron forma a un complejo, heterogéneo y versátil proceso de incesante movilización nacional mediante el cual la comunidad negra desafió al racismo institucional estadounidense bajo las consignas de raza y clase.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5538719-1512856324-8745.jpeg.jpg)