El bombardeo de la ciudad de Dresde por los Aliados en febrero de 1945 es considerado una de las peores atrocidades de la segunda guerra mundial. Miles de alemanes murieron víctimas de las bombas de los estadounidenses y británicos a pocos meses del fin de la guerra en Europa. En su momento el bombardeo no pasó de ser otro evento sangriento de una guerra brutal. Según Peter Feuerherd, no fue hasta la publicación de la novela Matadero cinco de Kurt Vonnegut en 1969, que la percepción del bombardeo de Dresde cambió.

Vonnegut, quien como prisionero de guerra fue testigo del bombardeo, reprodujo la brutalidad del ataque anglo-estadounidense. Escrito en medio de las protestas contra la guerra de Vietnam, Matadero cinco fue un éxito de ventas. A través de la ficción, Vonnegut no sólo rescató del olvido a Dresde, sino que planteó tres preguntas básicas: ¿Estaba moralmente justificado el bombardeo? ¿Fue un acto de venganza? ¿Fue necesario para acabar con la guerra en Europa? Esas tres preguntas siguen resonando y adquieren mayor fuerza en momentos en que Gaza sufre la acometida salvaje de un Israel que sabe y se siente impune. ¿Hemos aprendido algo los seres humanos desde que cayó la última bomba en Dresde? Pareciera que no.

Peter Feuerherd es profesor de periodismo en la Universidad de St. John’s en Nueva York y corresponsal del National Catholic Reporter. Es autor de Holy Land USA: A Catholic Ride Through America’s Evangelical Landscape (2006).

Cómo Matadero Cinco nos hizo ver el de Dresde

JSTOR Daily 13 de febrero de 2017

El bombardeo estadounidense y británico de Dresde, Alemania, que comenzó el 13 de febrero de 1945, fue visto en su día como una nota histórica a pie de página de una historia mucho más amplia. Después de todo, tuvo lugar cerca del final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, una guerra caracterizada por atrocidades demasiado numerosas para contarlas.

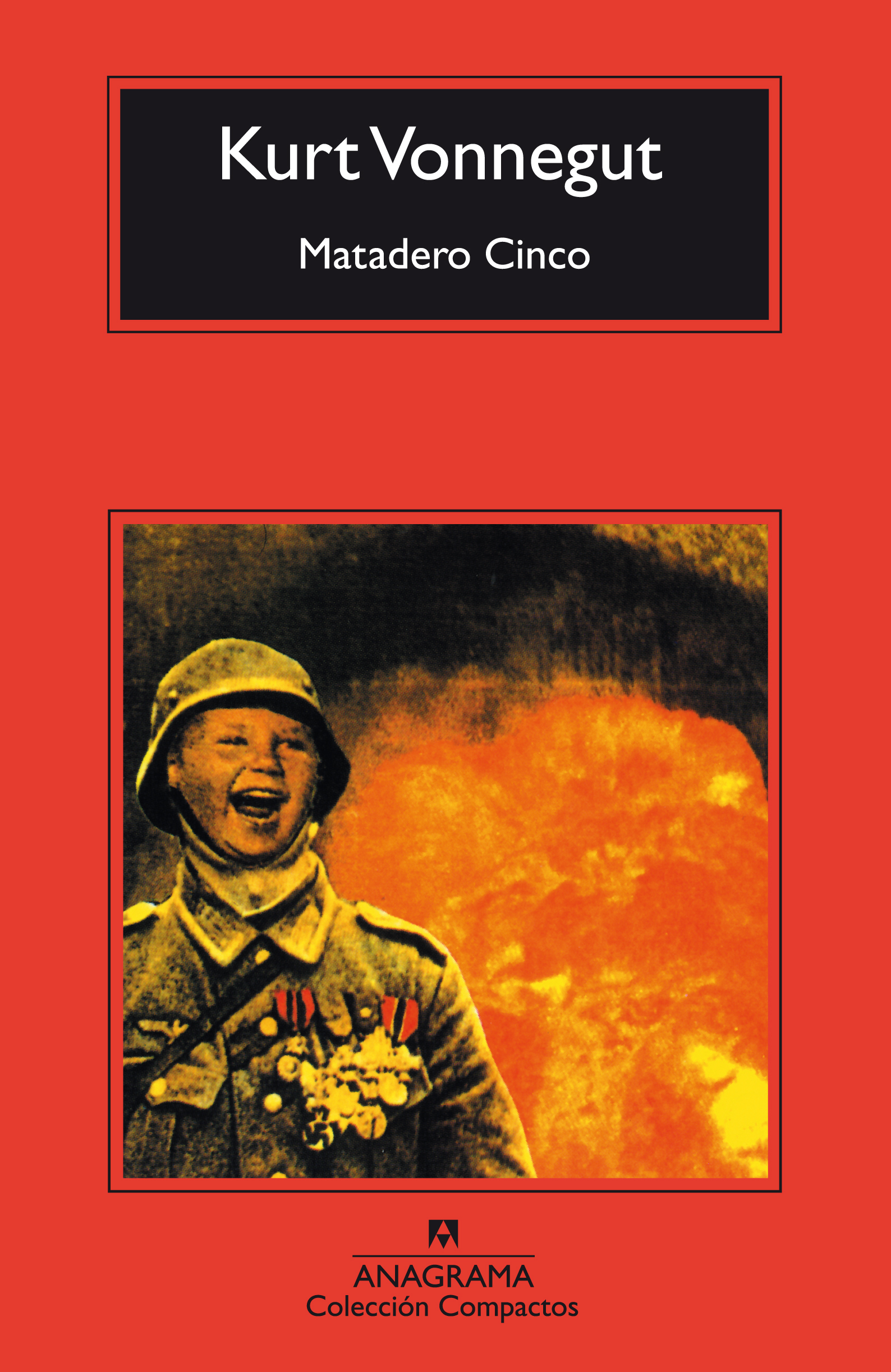

Luego vino la publicación en 1969 de una novela de ciencia ficción llamada Matadero Cinco de Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Había presenciado el bombardeo como prisionero de guerra estadounidense, y sobrevivió refugiándose en un armario de carne en la histórica ciudad alemana. La novela cuenta la historia de Billy Pilgrim, también prisionero de guerra estadounidense en Dresde, que viaja en el tiempo a través del espacio y comenta la barbarie con el discreto mantra de “Así va”.

La novela se convirtió en la obra icónica de Vonnegut, vendiendo más de 800.000 copias en los Estados Unidos. Fue ampliamente traducido. Matadero Cinco fue ampliamente leído como una declaración gráfica sobre la inutilidad de la guerra, capturando el espíritu de la época, cuando las protestas contra la guerra de Vietnam estaban en su cenit.

La novela se convirtió en la obra icónica de Vonnegut, vendiendo más de 800.000 copias en los Estados Unidos. Fue ampliamente traducido. Matadero Cinco fue ampliamente leído como una declaración gráfica sobre la inutilidad de la guerra, capturando el espíritu de la época, cuando las protestas contra la guerra de Vietnam estaban en su cenit.

“Todo esto sucedió, más o menos”, así es como Vonnegut introduce la novela.

La novela de Vonnegut reabrió una vieja herida: ¿estaba moralmente justificado el bombardeo de Dresde? ¿Fue simplemente un acto de venganza por los crímenes nazis, infligidos a civiles inocentes? ¿O era necesario poner fin a la guerra en Europa?

En la novela, Vonnegut describe a Billy Pilgrim como testigo del peor acto de violencia masiva en la historia europea, comparable al bombardeo atómico de Hiroshima. Citando una historia ampliamente publicada de la época, cifró las muertes de Dresde en 125.000.

Los historiadores cuestionaron las cifras de Vonnegut. Las muertes reales fueron mucho menores, alrededor de 25.000, y las cifras más altas fueron infladas por las afirmaciones de la propaganda nazi. Algunos argumentaron que Vonnegut había distorsionado los números para reforzar su punto de vista novelesco.

La crítica literaria Anne Rigney lo ve de otra manera. Vonnegut, señala, estaba trabajando con las cifras de víctimas aceptadas de su tiempo (las estimaciones posteriores y más bajas llegaron después de la publicación de la novela). Irónicamente, como testigo ocular del horror, Vonnegut sabía menos sobre el panorama general del bombardeo que los historiadores que tenían acceso a una gama más amplia de materiales.

Cádaver de una mujer en un refugio antiaéreo, Dresde, 1945. Wikipedia

Señala que la obra de Vonnegut no es historia. No pretende serlo. Presenta a un personaje que viaja en el espacio exterior y a través del tiempo. La novela es, más bien, una “memoria cultural” al definir un acontecimiento histórico a través de impresiones gráficas novelescas.

Aun así, Matadero Cinco tuvo consecuencias en el mundo real. Reabrió la investigación moral sobre los bombardeos de Dresde y, por implicación, sobre la guerra en general. El objetivo de Vonnegut era utilizar a los muertos de Dresde como una “presencia espectral” que informara a los vivos sobre las atrocidades de todas las guerras, con el punto de que “cada víctima colateral es demasiada”, escribe Rigney.

El resultado fue que el uso de la ciencia ficción por parte de Vonnegut y sus propios relatos de testigos oculares trajeron un feo evento de la Segunda Guerra Mundial a un mundo más dispuesto a escuchar sobre el impacto de la barbarie en tiempos de guerra 24 años después de los eventos reales.

Traducido por Norberto Barreto Velázquez