Es necesario reconocer que el afán expansionista de Donald J. Trump de las pasadas semanas tomó por sorpresa a muchos historiadores. Su énfasis en la adquisición de Groenlandia, la “recuperación” del canal de Panamá y la anexión de Canadá marcó el regreso a un tipo de imperialismo que caracterizó a Estados Unidos a finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX, y que parecía superado. No me malinterpreten, pues no estoy negando la naturaleza imperial de los Estados Unidos, sino que hace mucho tiempo los estadounidenses cambiaron la expansión territorial por la construcción de un imperio tecnológico-financiero-comercial, apoyado en una red de bases militares que le permite defender sus intereses y proyectar su poder a nivel global. De ahí que la última colonia adquirida por Estados Unidos fueran la islas Vírgenes en plena primera guerra mundial. Sin reparos Trump ha manifestado la “necesidad” de un crecimiento territorial como parte de su estrategia para “reconstruir” el poder estadounidense. Además, como los imperialistas de finales del siglo XIX, tiene bien claro cuáles son los territorios que apetece.

En esta entrevista del periodista Tim Murphy publicada en la revista Mother Jones, el historiador Daniel Immerwahr responde una serie de preguntas que buscan entender las expresiones de Trump desde una perspectiva histórica. En otras palabras, ¿cómo la historia del expansionismo estadounidense puede ayudar a explicar el neoimperalismo trumpista? ¿Marcan las expresiones de Trump un retroceso o el comienzo de algo nuevo? ¿Se le debe tomar en serio?

Para Immerwahr, Trump podría estar fanfarroneando o siguiendo su estrategia de crear escándalos que destantean a los liberales y venden muy bien entre sus seguidores, añadiría yo. Sin embargo, reconoce que Estados Unidos vive un “nuevo momento histórico en el que cosas nuevas son posibles”.

Al enfocar el deseo de Trump de cambiarle el nombre al golfo de México por golfo de América, Immerwahr hace comentarios muy interesantes sobre el uso del concepto América para referirse a Estados Unidos. Según él, este se comenzó a usar de forma dominante a partir de finales del siglo XIX y comienzos del XXI. Esto formó parte del giro imperialista estadounidense. En otras palabras, de un sentido de imperio. Nuevamente vemos a Trump conectado con el pasado imperial de Estados Unidos.

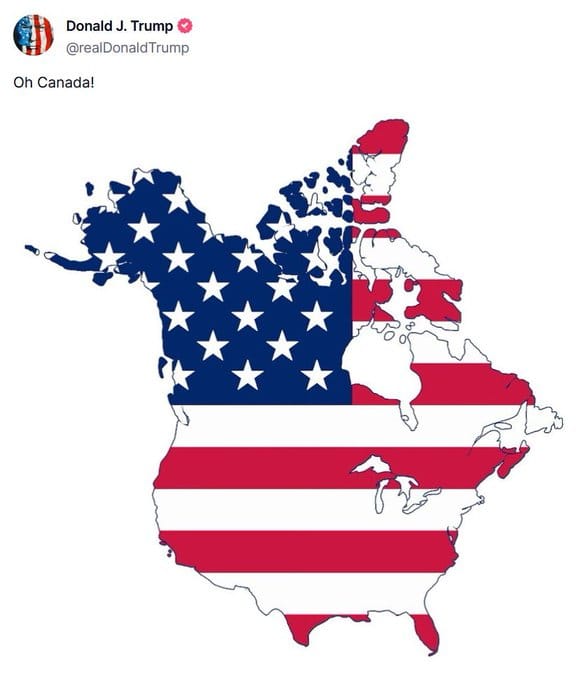

La ausencia de Puerto Rico en el mapa de su America soñada que Trump compartió en la red social Truth Social le sirve a Immerwahr para reflexionar sobre uno de los elementos básicos del imperialismo estadounidense: el deseo de adquirir territorios, pero no a los pobladores de estos, sobre todo, si no son blancos. Al dejar a Puerto Rico fuera de su mapa y a haber planteado el deseo de vender a la isla, Trump coincide con la mentalidad racista de los imperialistas del siglo XIX y principios del XX, a quienes les quitaba el sueño la composición étnica de los territorios adquiridos por Estados Unidos.

Immerwahr no nos da un respuesta precisa a la preguntas planteadas sobre la seriedad de los arranques expansionistas de Trump. Para él, el patrioterismo de Trump podría ser otra de sus provocaciones o un interés real. Curiosamente señala que, de ser los segundo, las aspiraciones del nuevo inquilino de la Casa Blanca podrían formar parte de un renacer imperialista del que la guerra en Ucrania y las ambiciones chinas sobre Taiwán son claros ejemplo. De esta forma estaríamos entrando en una nueva era de anexiones territoriales de las que las aspiraciones de Trump formarían parte.

Una cosa es clara para Immerwahr: contrario a sus predecesores demócratas y republicanos que lo negaron sistemáticamente, Trump no tiene reparos en reconocer que Estados Unidos es un imperio.

Immerwahr es profesor de historia en Northwestern University y autor del libro How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (2019) que reseñé en diciembre de 2020 (El imperio invisible).

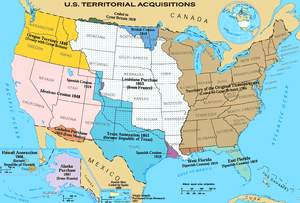

Para un enfoque más detallado del proceso de expansión territorial estadounidense ver mi ensayo El expansionismo norteamericano, 1783-1898.

Lo que la historia de la expansión estadounidense puede decirnos sobre las amenazas de Trump

Tim Murphy

Mother Jones, 15 de enero de 2025

El presidente electo, que impulsó una invasión de México durante su primer mandato, ha pasado el mes previo a la toma de posesión de la próxima semana publicando sobre invitar a Canadá a unirse a Estados Unidos, negándose a descartar el uso de la fuerza militar para obligar a Dinamarca a vender (o regalar) Groenlandia, y prometiendo recuperar la Zona del Canal de Panamá, que Estados Unidos devolvió como parte de un tratado de 1979. Los republicanos y sus aliados se han alineado rápidamente. Charlie Kirk y Donald Trump Jr. hicieron recientemente un viaje de un día a Groenlandia. Algunos conservadores han comparado las adquisiciones amenazadas con la compra de Alaska y Luisiana.

¿Es esto solo un retroceso al pasado de construcción del imperio del país, o un reconocimiento de algo nuevo? Para entender la retórica reciente de Trump, hablé con Daniel Immerwahr, profesor de historia en la Universidad Northwestern, cuyo libro de 2019, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, contó la historia del pasado y el presente imperial de Estados Unidos.

¿Qué pensó cuando vio al presidente electo Trump anunciar que estaba pensando en adquirir, de alguna manera, Groenlandia?

Aquí vamos de nuevo. Literalmente hemos pasado por todo esto. Lo hemos pasado en Estados Unidos: los presidentes solían estar muy interesados en adquirir terrenos estratégicamente relevantes, y hay una larga historia de eso. También lo hemos pasado con Donald Trump, porque lo hizo durante su primer mandato: amenazó con adquirir Groenlandia. Se consultó a los historiadores: “¿Ha ocurrido esto? ¿Cuándo fue la última vez que sucedió esto? Fue mucha fanfarronería entonces, o al menos creo que fue mucha fanfarronada; no tuve la sensación de que el ejército estadounidense estuviera preparado para hacer algo dramático, y no tuve la sensación de que el gobierno danés estuviera interesado en vender. Así que la pregunta sigue siendo en este momento: ¿Es este un nuevo momento histórico en el que nuevas son posibles? (Y hay algunas razones para pensar que tal vez, sí lo es). ¿O es que Trump está haciendo lo que Trump hace tan bien, que es acabar con los liberales proponiendo cosas escandalosas?

Antes de Trump, ¿estaba Groenlandia en el radar de los imperialistas estadounidenses?

Groenlandia se volvió mucho más interesante para los Estados Unidos en la era de la aviación, porque si dibujas las rutas aéreas más cortas desde los Estados Unidos continentales hasta, por ejemplo, la Unión Soviética, encontrarás que algunas de ellas pasaban cerca o sobre Groenlandia. Así que Groenlandia fue un sitio importante de la Guerra Fría.

Estados Unidos almacenó armas nucleares allí. También sobrevoló armas sobre Groenlandia: lo que eso significa es que los aviones se mantendrían en el aire y listos para entrar en acción en caso de que sonara la alarma. La película Dr. Strangelove tiene imágenes de este tipo de aviones sobre Groenlandia.

También hay una historia de accidentes nucleares en Groenlandia.

¿Accidentes nucleares?

En la década de 1950, tres aviones realizaron aterrizajes de emergencia en Groenlandia mientras transportaban bombas de hidrógeno. Algo salió mal y los aviones se detuvieron. En 1968, un B-52 que volaba sobre Groenlandia con cuatro bombas de hidrógeno Mk-22, no aterrizó, simplemente se estrelló a más de 500 millas por hora, dejando un rastro de escombros de cinco millas de largo. El combustible para aviones se incendió y todas las bombas explotaron. Lo que sucedió en estos casos es que las bombas fueron destruidas en el proceso, pero no detonaron. Sin embargo, estuvo a punto de fallar, y es pensable, dada la forma en que se construyeron las bombas, que estrellarse contra el hielo a 500 millas por hora habría hecho detonar. Se puede ver por qué [tener armas nucleares en la isla] era una propuesta peligrosa para los europeos, y particularmente para la gente de Groenlandia.

Otro de los grandes anuncios recientes fue la promesa de Trump de cambiar el nombre del Golfo de México por el de “Golfo de América”. Usted escribió en su libro que el término América para referirse a Estados Unidos solo se puso realmente de moda en la época de Theodore Roosevelt. ¿Cuál es la conexión entre ese nombre y este sentido de imperio?

Hubo alguna discusión, no mucha, pero sí alguna, en los primeros años de la república sobre cuál debería ser la abreviatura para referirse a Estados Unidos. Columbia era un término literario que la gente usaba y aparecía en muchos himnos del siglo XIX. Freedonia fue probada, como “la tierra de la libertad”, pero lo interesante es que, desde nuestra perspectiva, la taquigrafía obvia -”América”- no fue la dominante para referirse a los Estados Unidos a lo largo del siglo XIX. Una razón para ello es que los líderes de los Estados Unidos eran plenamente conscientes de que estaban ocupando una parte de América y que también había otras partes de América. Había otras repúblicas en las Américas.

No es hasta finales del siglo XIX que se empieza a ver a “América” como la abreviatura dominante. Una gran razón para ello es que justo a finales del siglo XIX, los Estados Unidos comenzaron a adquirir grandes y populosos territorios de ultramar, de modo que gran parte de la taquigrafía anterior (la Unión, la República, los Estados Unidos) parecían descripciones inexactas del carácter político del país.

Así que “América” es un giro imperialista en dos sentidos. Una es que sugiere que este único país de las Américas es de alguna manera la totalidad de las Américas, como si los alemanes decidieran que en adelante iban a ser “europeos” y que todos iban a tener que ser ingleses-europeos o franceses-europeos o polacos-europeos, y solo los alemanes eran “europeos”. También es imperialista en el sentido de que surgió en un momento en que la gente se preguntaba cuál sería el carácter político del país, y se preguntaba si la adición de colonias hacía que Estados Unidos ya no fuera realmente una república, una unión o un conjunto de estados.

Trump dijo recientemente que iba a “traer de vuelta el nombre de Mount McKinley porque creo que se lo merece”. ¿Cómo se compara lo que está haciendo, y la forma en que habla de lo que está haciendo, con lo que William McKinley y Theodore Roosevelt decían y hacían a finales del siglo XIX?

En cierto modo, se compara claramente, porque hubo una larga época en la historia de Estados Unidos, y no fueron solo McKinley y Roosevelt; fue hasta ellos y un poco después, donde, cuando Estados Unidos se hizo más poderoso, se hizo más grande. El poder se expresaba en la adquisición de territorio. Los Estados Unidos se anexionaron tierras, tierras contiguas de la Compra de Luisiana y tierras de ultramar; Filipinas, Puerto Rico, Guam, etc. Esa es la historia que Trump está invocando, y en la que se imagina participando.

La época de la colonización estadounidense de ultramar fue también una época en la que otras “grandes potencias” colonizaban territorios de ultramar en África y Asia. No me queda claro si estamos en el momento en el que vamos a empezar a ver a los países más poderosos adquiriendo colonias, como solían hacer. Trump está apuntando a ese momento, pero no me queda claro, por ejemplo, cuántos en su base están realmente fuertemente motivados por esto. No está claro a cuántos otros republicanos les importa esto más allá de preocuparse por la lealtad a los caprichos de Trump. Por lo tanto, no es obvio que se trate de un movimiento social, sino más bien de una forma de acabar con los oponentes de Trump y posiblemente distraerlos.

¿Hay alguna lección para Trump y el gobierno de Trump sobre cómo terminó esa era de expansionismo y la reacción violenta a ella?

Hay dos cosas que hicieron que un imperio de esa naturaleza colonial fuera mucho más raro a finales del siglo XX. Una fue una revuelta anticolonial global que comenzó en el siglo XIX pero llegó a su clímax después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, y simplemente hizo mucho más difícil para los posibles colonizadores mantener o tomar nuevas colonias. La otra es que los países poderosos, incluido Estados Unidos, buscaron encontrar nuevos caminos para la proyección de poder que no implicaran la anexión de territorios, en parte porque se dieron cuenta de que un mundo en el que cada país garantizara su seguridad y expresara su poder mediante la anexión de territorios crearía una situación en la que los países grandes chocarían entre sí.

Así que las dos lecciones, yo diría, de la Era del Imperio son que es extremadamente cruel con aquellos que son colonizados porque están sujetos a un gobierno extranjero que generalmente no tiene sus intereses en mente. Y es extraordinariamente peligroso porque enfrenta a las grandes potencias entre sí de una manera que puede conducir rápidamente a la guerra. Y si las guerras de principios de la primera mitad del siglo XX fueron guerras extraordinariamente sangrientas, al menos, no implicaron intercambios nucleares de ambos bandos, como podrían implicar las versiones del siglo XXI de esas guerras.

La administración Trump en la primera vuelta pareció toparse con otra parte de esto, que era que realmente no le gustaba tener que lidiar con Puerto Rico. No le gustaba tener que financiar la reconstrucción de Puerto Rico después del huracán María. De hecho, había gente que se refería a Puerto Rico como un país diferente. ¿Es eso parte de este alejamiento del imperio, de no querer tener que lidiar con la gente que has colonizado?

Siempre ha habido una discusión, incluso entre los imperialistas, sobre si las cargas del imperio valen las ventajas. El racismo a veces ha actuado como una ruptura en el imperio. Encontrarás momentos, incluso en la historia de Estados Unidos, en los que a los expansionistas les gustaría, por ejemplo, poner fin a una guerra entre Estados Unidos y México tomando una gran parte de México, y luego los racistas dirán: “Oh no, no, no; si tomamos más de México, por lo tanto, tomaremos más mexicanos”. Y ese tipo de debate se repitió una y otra vez en el siglo XIX en Estados Unidos y a principios del siglo XX.

Esta tendencia se puede ver en la mente de Trump, porque por un lado, expresa una predisposición expansionista, y amenaza con mover las fronteras de EE.UU. hacia varios otros lugares del hemisferio occidental. Por otro lado, Trump imagina claramente a Estados Unidos como un lugar contiguo alrededor del cual se puede construir un muro alto. Y es bastante hostil con los extranjeros.

Cuando habla de Puerto Rico durante la primera administración, tenemos informes desde dentro de la administración Trump que dicen que Trump quería vender a Puerto Rico. Así que esos son, de alguna manera, los dos impulsos enfrentados en las mentes de Trump, y en realidad coinciden bastante bien con algunos de los impulsos dominantes en los líderes estadounidenses del siglo XIX y principios del XX: por un lado, el deseo de crear más territorio; por otro lado, una profunda preocupación por incorporar a más personas, particularmente personas no blancas, dentro de los Estados Unidos.

Me encantaría decir que esa es una situación del pasado, y que estamos muy más allá de ella, porque ya no tenemos los deseos de anexión ni el racismo excluyente que la impulsó. Pero Trump parece estar resucitando, al menos instintivamente, a ambos.

¿Viste el mapa que compartió en Truth Social?

Lo estoy mirando ahora. Así que hablemos de este mapa. Este es un mapa de los Estados Unidos que imagina que sus fronteras se extienden hasta Canadá y abarcan a Canadá, pero también imagina que las fronteras de los Estados Unidos no incluyen a Puerto Rico. Así que es una visión de un Estados Unidos más grande y un Estados Unidos más blanco. Y aborda la contradicción del imperio: tanto el deseo de los imperialistas de expandir el territorio, como el deseo de curar poblaciones dentro de ese territorio. Y se puede ver esto como la ambición de Trump de tener un Estados Unidos más grande, pero también un Estados Unidos más pequeño.

Has usado el término “puntillista“ para describir cómo se ve el imperio estadounidense ahora, con una serie de bases militares y pequeños territorios repartidos por todo el mundo. Ha habido una aceptación dentro del gobierno de los Estados Unidos de la conveniencia de ese acuerdo. ¿Cuánto de esto es solo una forma de hablar de la fuerza, separada de un plan real para hacer cualquier cosa?

Trump a menudo tiene un juicio político terrible, pero tiene instintos políticos interesantes, y a menudo es capaz de ver posibilidades que otros políticos han rechazado, de ver cosas que parecen escandalosas pero que en realidad podrían asegurar una base de votantes. Una gran pregunta sobre todo este patrioterismo que Trump ha estado imponiendo es si se trata simplemente de otra de sus provocaciones y otra de sus idiosincrasias, o si está respondiendo a algo real.

Si se argumentara que Trump está respondiendo a algo real —que las condiciones y las posibilidades reales han cambiado, y que de hecho podríamos estar entrando en una nueva era de imperio territorial, donde el poder se expresa mediante la anexión de grandes franjas de tierras, ni siquiera solo controlando pequeños puntos— señalaría a Ucrania, y señalaría las ambiciones de China de apoderarse de Taiwán. Se podría decir que estamos entrando en una nueva era de anexiones, y que Trump lo percibe y a menudo admira el tipo de fuerza que se expresa en las anexiones semicoloniales, y lo ve como un futuro potencial para Estados Unidos.

Me llama la atención eso, porque a los políticos de ambos partidos les gusta decir que no somos un imperio, lo que significa, al menos, que no nos gusta pensar en nosotros mismos como un imperio. Y el tipo de Trump dice, en realidad, tal vez sí, y hay una corriente subterránea en la que la gente quiere pensar en sí misma como tal.

Básicamente, desde William McKinley, casi todos los presidentes han dicho alguna versión de “Estados Unidos no es un imperio; No tenemos ambiciones territoriales, no codiciamos el territorio de otros pueblos”. Presidente tras presidente, demócratas y republicanos, todos dicen alguna versión de eso. Excepto por Trump. Esa es una piedad liberal sostenida no solo por los demócratas, sino también por los republicanos, en la que Trump parece no tener ninguna inversión. Y creo que en ese sentido, tiene razón, porque cuando los presidentes han dicho que no somos un imperio, siempre han estado hablando desde un país que tiene colonias y tiene territorios. Así que Trump tiene razón al no seguir ese camino, aunque creo que es bastante peligroso que vea la negación del imperio no solo como algo de lo que burlarse, sino como algo que debe ser rechazado desafiantemente por la búsqueda de ambiciones territoriales.

Traducido por Norberto Barreto Velázquez